Patricia Giudice's Story

|

My family, Singapore childhood & escape to Australia

My name is Patricia Giudice, nee Edwards of Fremantle, Western Australia, formally of Upper East Coast Rd, Singapore, from 1935 to 1942. In February 1942 with my father, grandmother and my sister I narrowly escaped the Japanese at St John’s Island, Singapore and we eventually reached Western Australia. Here is the story of my family and that escape.kers children. It was an adventure going up by car to the Plantation. It sounds ideal from my description but as with all stories there are downsides.

My Family History Three generations of my family were born in Singapore. They were my paternal grandmother, my father and mother, and myself. |

My Paternal Grandmother: Allen & Edwards Families

My grandmother Annie Beatrice Allen was born in 1880. Her parents were Christina Elizabette and Charles Martin Allen. I believe Christina was French or part French. They married in 1860. To date I've been unable to decipher her maiden name on their marriage certificate. Annie's father was part of the Allen family, known in some writings about Singapore as the 'Allen Brothers' who arrived in Singapore before 1860.

The Allen brothers worked in various professions but I believe great grandfather Charles was an engineer. As well, the brothers owned an estate called "Perseverance Estate". The information I obtained from Charles' death certificate in St Andrews Cathedral's Archives stated he was a patchouli plantation owner. Others have said the plantation grew grasses such as lemon grass. Patchouli was and is a very popular incense and fragrant oil in India and a base for French perfumes.

Later as the Allen brothers married and had children, the family brought cows to Singapore from Ireland to provide milk for their families and those of their workers. They also brought out horses for work and pleasure and other farm animals. They brought seeds for fruits and vegetables to support all the needs of those living on the Estate.

Annie and her fortunate siblings played on huge tricycles, amongst other toys, with the jungle almost on their doorstep. The girls owned beautiful dolls and wore long back stockings under their frilly petticoats and dresses, and wide brim hats. Growing up, Annie spoke French and English at home and probably added Malay, a Chinese dialect and Tamil to her home languages. When she began her schooling, she went to the French Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, now a complex of restaurants and shops called "Chijmes."

After she finished school, Annie went to Paris and enrolled in a school of classical music. In her late twenties, during a holiday in Ireland, Annie met her future husband Charles Walter Edwards and married so did not further her piano studies. Charles was an Irish engineer. My aunt Clare told me her mother had two wedding ceremonies, the first of which took place in Singapore and the second in Dublin. Because the two ceremonies were held in two different climates, Annie had two different wedding dresses and wedding cakes. For their honeymoon, my grandparents went to Blarney Castle in Ireland where Annie kissed the Blarney stone. The myth is if you kiss the almost impossible to reach Blarney Stone and make a wish then your wish is sure to come true. It did so for Granny! When she kissed the Blarney Stone she wished for her first born to be a son and indeed a son, Charles Patrick Edwards was born in Dublin and from that moment on Granny called my father “Blessing”. It was a hard act to follow. As a child, I had to be satisfied with being called "fish cake" I presume it meant I was delicious!... Australian style fishcakes are delicious!

Annie's other five children, Marguerite, Kathleen, Laurie and Norman and Clare were born in Singapore. Norman was only 18 months old when he died from an infection and Clare was born a few months after the death of her father.

My Paternal Grandfather: Charles Walter Edwards

Charles lived with his parents and two brothers in Dublin until in the 1900s. He then came to Singapore. His father had been an engineer. His mother, from photos I have seen, was a true Irish matriarch, widowed at some point when her sons were young adults. She was an unsmiling woman.

Grandfather Charles died in his forties, from malaria. This tragedy left Annie alone in Singapore, without any family to assist her support their six children the last of whom hadn't been born. Because life must go on, not long after the birth of her last child Clare, Granny began teaching music and French at her old school, the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, in order to support her children. All her daughters were to attend the school and her sons attended the De la Salle Brothers School for Boys, St. Joseph’s.

My grandmother Annie Beatrice Allen was born in 1880. Her parents were Christina Elizabette and Charles Martin Allen. I believe Christina was French or part French. They married in 1860. To date I've been unable to decipher her maiden name on their marriage certificate. Annie's father was part of the Allen family, known in some writings about Singapore as the 'Allen Brothers' who arrived in Singapore before 1860.

The Allen brothers worked in various professions but I believe great grandfather Charles was an engineer. As well, the brothers owned an estate called "Perseverance Estate". The information I obtained from Charles' death certificate in St Andrews Cathedral's Archives stated he was a patchouli plantation owner. Others have said the plantation grew grasses such as lemon grass. Patchouli was and is a very popular incense and fragrant oil in India and a base for French perfumes.

Later as the Allen brothers married and had children, the family brought cows to Singapore from Ireland to provide milk for their families and those of their workers. They also brought out horses for work and pleasure and other farm animals. They brought seeds for fruits and vegetables to support all the needs of those living on the Estate.

Annie and her fortunate siblings played on huge tricycles, amongst other toys, with the jungle almost on their doorstep. The girls owned beautiful dolls and wore long back stockings under their frilly petticoats and dresses, and wide brim hats. Growing up, Annie spoke French and English at home and probably added Malay, a Chinese dialect and Tamil to her home languages. When she began her schooling, she went to the French Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, now a complex of restaurants and shops called "Chijmes."

After she finished school, Annie went to Paris and enrolled in a school of classical music. In her late twenties, during a holiday in Ireland, Annie met her future husband Charles Walter Edwards and married so did not further her piano studies. Charles was an Irish engineer. My aunt Clare told me her mother had two wedding ceremonies, the first of which took place in Singapore and the second in Dublin. Because the two ceremonies were held in two different climates, Annie had two different wedding dresses and wedding cakes. For their honeymoon, my grandparents went to Blarney Castle in Ireland where Annie kissed the Blarney stone. The myth is if you kiss the almost impossible to reach Blarney Stone and make a wish then your wish is sure to come true. It did so for Granny! When she kissed the Blarney Stone she wished for her first born to be a son and indeed a son, Charles Patrick Edwards was born in Dublin and from that moment on Granny called my father “Blessing”. It was a hard act to follow. As a child, I had to be satisfied with being called "fish cake" I presume it meant I was delicious!... Australian style fishcakes are delicious!

Annie's other five children, Marguerite, Kathleen, Laurie and Norman and Clare were born in Singapore. Norman was only 18 months old when he died from an infection and Clare was born a few months after the death of her father.

My Paternal Grandfather: Charles Walter Edwards

Charles lived with his parents and two brothers in Dublin until in the 1900s. He then came to Singapore. His father had been an engineer. His mother, from photos I have seen, was a true Irish matriarch, widowed at some point when her sons were young adults. She was an unsmiling woman.

Grandfather Charles died in his forties, from malaria. This tragedy left Annie alone in Singapore, without any family to assist her support their six children the last of whom hadn't been born. Because life must go on, not long after the birth of her last child Clare, Granny began teaching music and French at her old school, the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, in order to support her children. All her daughters were to attend the school and her sons attended the De la Salle Brothers School for Boys, St. Joseph’s.

|

My Maternal Grandfather; Bertie Kirwan

Herbert Stewart Kirwan known as Bertie, was born in 1879 into a large family, during harsh economic times. The family lived in Melbourne. It was the custom at the time, for some large families who were struggling to feed their children, to send them to other family members to be cared for. Bertie was only ten years old when sent he was to work for an Uncle on a vast cattle station in North Queensland. Here wild horses abounded. It was similar to the endless horizon of the flat land of the Australian 'Outback'. He probably never saw his parents or siblings for many years and because Bertie lived in such a remote part of Australia he was deprived of an education... that is until he arrived in Johore Bahru, Malaya. At the age of nineteen, Bertie accompanied a consignment of those wild horses on a sailing ship, sailing from Queensland bound for the Sultan of Johore. I can't imagine Bertie's reactions to be travelling on a sailing ship watching spinnakers ballooning into the wind, flying above all those horses and what of the horses themselves? At times it must have been a nightmare for all on board. The vast horizon of an endless ocean. |

Bertie must have been relieved when he caught sight of the exotic island called Singapore where sampans and sailing ships nestled side by side. Fortunately for Bertie, there was no Causeway to the Malayan mainland so he didn't have to contemplate ushering wild horses through the young city of Singapore. The ship would have gone directly to Johore and Bertie would have delivered the horses to a pre-arranged stockyard on the beach in front of the Palace.

When Bertie arrived at the Palace, he would have lacked many social graces but what he lacked in graces he made up for with his charm. For some reason the Sultan took a shine to him and invited him to stay in the country and live in the Palace grounds while he broke-in the horses in preparation for racing. As well, the Sultan offered to pay for Bertie's education by correspondence, if he wished to stay. Bertie stayed.

During those early years at the palace, Bertie wouldn't have had a problem breaking in wild-horses or using rifles, for he had become a multi-skilled young man while living on the Station. Soon he became a very successful race horse trainer. Along the way, he must have acquired some social skills, for soon he was included in the Sultan's family's social events and those at Government House and invited on hunting jaunts into Borneo, and Sumatra.

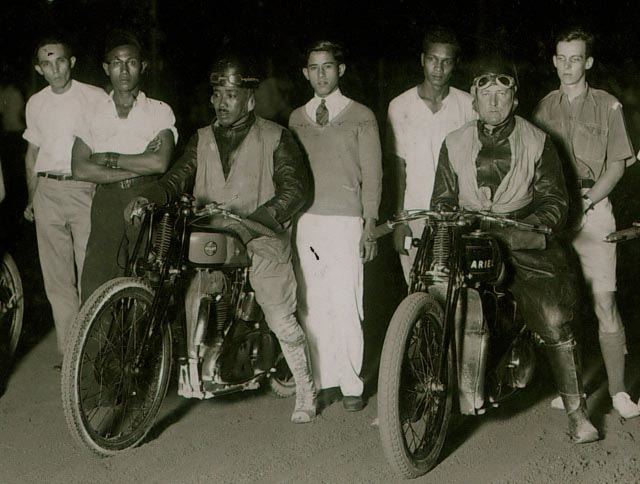

Other interests Bertie shared with the Sultan’s family were racing cars and motorbikes. I have a photo of him and one of the Princes about to race their motorbikes on the beach with their 'seconds'. In it the Prince's 'second' is a young son. The Prince is dressed in leathers, his son is dressed quite formally, wearing a shirt and tie and a pullover and my young uncle Pat, my mother's older brother, is Grandfather's 'second'. He is dressed in casual clothes while the locals were dressed even more casually.

When Bertie arrived at the Palace, he would have lacked many social graces but what he lacked in graces he made up for with his charm. For some reason the Sultan took a shine to him and invited him to stay in the country and live in the Palace grounds while he broke-in the horses in preparation for racing. As well, the Sultan offered to pay for Bertie's education by correspondence, if he wished to stay. Bertie stayed.

During those early years at the palace, Bertie wouldn't have had a problem breaking in wild-horses or using rifles, for he had become a multi-skilled young man while living on the Station. Soon he became a very successful race horse trainer. Along the way, he must have acquired some social skills, for soon he was included in the Sultan's family's social events and those at Government House and invited on hunting jaunts into Borneo, and Sumatra.

Other interests Bertie shared with the Sultan’s family were racing cars and motorbikes. I have a photo of him and one of the Princes about to race their motorbikes on the beach with their 'seconds'. In it the Prince's 'second' is a young son. The Prince is dressed in leathers, his son is dressed quite formally, wearing a shirt and tie and a pullover and my young uncle Pat, my mother's older brother, is Grandfather's 'second'. He is dressed in casual clothes while the locals were dressed even more casually.

|

There is another photo of Bertie, showing a collection of his trophies - he must have been a very accomplished marksman.

|

Bertie married Robyna Duncan Batchelor in 1910. She lived in Singapore with her family. The couple married in St Andrew's Cathedral and went back to live in the Palace grounds where Patrick and Lucy were born.

I have a photo of Robyna in her Edwardian riding clothes holding her crop. The clothes look very heavy for the humidity of Singapore. She is wearing her hat and long skirt, a white shirt and a short jacket. I wonder how she filled her days in the Palace grounds, dressed in Edwardian clothes? Unfortunately, Robyna, like her mother, my Great Grandmother, died suddenly, > Robyna from blood poisoning when Lucy was four and Patrick approximately nine years of age. She was the second mother in our family to die at a young age, leaving young children. |

My Father; Charles Patrick Edwards

My father Charles Patrick was born in Dublin in 1910. My grandparents must have planned to live in Dublin for a couple of years before returning to Singapore, for by the time they did, my father was twelve months of age. I have a photo of Granny Annie in a beautiful Edwardian dress with my father on her knee. He too is wearing a dress. Probably it is his first birthday photo. She looks stunning with her bundle of hair swept up.

My father Charles Patrick was born in Dublin in 1910. My grandparents must have planned to live in Dublin for a couple of years before returning to Singapore, for by the time they did, my father was twelve months of age. I have a photo of Granny Annie in a beautiful Edwardian dress with my father on her knee. He too is wearing a dress. Probably it is his first birthday photo. She looks stunning with her bundle of hair swept up.

|

In Singapore Pat attended the French De La Salle School for boys, as did his younger brother Laurie. The beautiful building in Bras Basah Rd that once housed the school is now a museum. At school, Pat became friends with some of the Princes from the Palace in Johore. Over the years he was invited to stay for school holidays. Friendships made then were to last until the Japanese Occupation.

While visiting the Palace in the school holidays, Pat came under the influence of Lucy's father, Bertie Kirwan. Bertie taught Pat to shoot, ride a motorbike and later to race cars. Later still, he became Bertie's son-in-law! He also had a close relationship with Lucy and her brother Patrick who was about the same age. Since an adolescent, he had been included in the Royal family shooting parties to Sumatra and Borneo. I'm sure the skills my father learnt in those early days by the side of my grandfather Bertie, were to be of paramount importance to our escaping safely from the Japanese in Sumatra. I am sure my father, through belonging to the various clubs in Singapore, would have had many social gatherings with the Malayan Volunteers because his father in-law Bertie was an enthusiastic member of the Volunteers in Johore Bahru. and in Singapore. I have two, teaspoon-trophies are marked S.R.A (V) and S.V.R.A. - Singapore Royal Artillery [Volunteers], and Singapore Volunteer Rifle Association. He is also on a 1920s photo of the Singapore Volunteers machine gun company. Patrick met Lucy in the Palace grounds when she was a child of nine and he was thirteen. They married when she was nineteen. By now Pat was a mechanical engineer and could support a wife and children. Before his father died, the plan had been that after he finished senior school he would attend Trinity College in Dublin and study Mechanical Engineering, but plans changed after the death of his father. Because Granny had yet to give birth to her youngest child, Pat chose to stay behind and help his mother care for his brood of siblings. |

After he finished his schooling Pat was able to fulfil his wish to become a mechanical engineer because Trinity College offered him the opportunity to do so through a Correspondence course.

My Mother: Lucy Amy Kirwan

Lucy was born in 1914. She was the youngest of two children. Her brother was also named Patrick. For most of her childhood the only home she knew was within the huge grounds where her father trained horses for the Sultan.

My Mother: Lucy Amy Kirwan

Lucy was born in 1914. She was the youngest of two children. Her brother was also named Patrick. For most of her childhood the only home she knew was within the huge grounds where her father trained horses for the Sultan.

|

I am looking at a photo of the children dressed in white. It appears to be a special occasion. I see a three-year old Lucy and a seven-year-old Patrick standing in front of towering, thick, lush vegetation. She is wearing the sweetest little dress that sits over layered petticoats, and underneath the petticoats are her long, white socks and black shoes the look is topped off with a cute bonnet...so different to what Lucia and I were wearing in the same climate - we wore rompers or light-airy dresses. Patrick is wearing a white longish jacket, his white shirt is set-off by a black bow tie. Below his knee- length, white shorts are long white socks and black shoes. In this photo, Lucy looks a sombre child.

Lucy was four years old when her mother Robyna died. The reason given to me was that Robyna had picked a pimple on her face, prior to an outing and while outside, the rain had wet the black net veil on her hat and the dye ran, touching her face. Within a very short time, she developed blood poisoning and died. Robyna was young- mother- number-two,to die. She was in her mid-twenties. Grandfather Bertie took the children to his sister's in Melbourne where they lived until Bertie brought them back to Johore. Lucy was then nine. For the moment I have no idea where she went to school in Johore or where she worked in Singapore, but soon after she had begin working, Pat and Lucy married and then went to live with Granny. Lucy was nineteen and Pat twenty-three. |

My History: Patricia Robyna Edwards (Giudice.)

I was Pat and Lucy's first child, born June 4th 1935. Living in Granny's home was Ah Khan, the amah my father had had as a baby and so she became my amah. I called her Aunty Amah.

In October 1937, the Edwards family basked joyously in the birth of my sister Lucia, not realising that in a few short weeks they would be sitting wordlessly on 'the dark side of the Moon’ stricken with grief.

From the time Lucy could understand the myth that "things happened in three's" she anticipated that she too would die when her children were young. She spoke of this fear to anyone who would listen. Sure enough, her 'self fulfilling prophecy' began to unfold when she attended her postnatal check up six weeks after Lucia's birth. When Destiny whispered Lucy's name, Lucia was six weeks old, Lucy was twenty three and I was two. Lucy had no choice but to open the wings behind her ears and leave us.

My sister and I were the third generation of children to 'lose' their mothers before the age of ten. On the Fateful day Lucy left for her doctor's appointment, Granny and I sat on the front steps, waving goodbye to her and baby Lucia and her Amah. Within minutes, the car returned. Lucy took off her rings and bracelets and said to Granny, words to the affect that if she didn't 'return', the jewellery was for me.

It appears Lucy did some shopping before her doctor's appointment as if she anticipated returning home. Her shopping bags were on the floor of the surgery. Because her appointment was a routine one, Lucy went alone. The expected pelvic examination had been painful and so that he could continue with the examination, the doctor suggested to Lucy he give her a whiff of chloroform. Did she realize her life was in imminent danger if she agreed to this next step? I hope not. She was alone with no one there to hold her hand or reassure her and tell her how much we loved and needed her. Obviously, no one anticipated that one drop of pain-relief on a mask would stop Lucy's delicate heart and that she would die in the surgery.

I wonder how Lucia's Amah coped with the immediate distress of looking after a baby and taking her home to break the news to Granny, who would have been home by herself. What confusion must have ensued for my devastated family.

I was Pat and Lucy's first child, born June 4th 1935. Living in Granny's home was Ah Khan, the amah my father had had as a baby and so she became my amah. I called her Aunty Amah.

In October 1937, the Edwards family basked joyously in the birth of my sister Lucia, not realising that in a few short weeks they would be sitting wordlessly on 'the dark side of the Moon’ stricken with grief.

From the time Lucy could understand the myth that "things happened in three's" she anticipated that she too would die when her children were young. She spoke of this fear to anyone who would listen. Sure enough, her 'self fulfilling prophecy' began to unfold when she attended her postnatal check up six weeks after Lucia's birth. When Destiny whispered Lucy's name, Lucia was six weeks old, Lucy was twenty three and I was two. Lucy had no choice but to open the wings behind her ears and leave us.

My sister and I were the third generation of children to 'lose' their mothers before the age of ten. On the Fateful day Lucy left for her doctor's appointment, Granny and I sat on the front steps, waving goodbye to her and baby Lucia and her Amah. Within minutes, the car returned. Lucy took off her rings and bracelets and said to Granny, words to the affect that if she didn't 'return', the jewellery was for me.

It appears Lucy did some shopping before her doctor's appointment as if she anticipated returning home. Her shopping bags were on the floor of the surgery. Because her appointment was a routine one, Lucy went alone. The expected pelvic examination had been painful and so that he could continue with the examination, the doctor suggested to Lucy he give her a whiff of chloroform. Did she realize her life was in imminent danger if she agreed to this next step? I hope not. She was alone with no one there to hold her hand or reassure her and tell her how much we loved and needed her. Obviously, no one anticipated that one drop of pain-relief on a mask would stop Lucy's delicate heart and that she would die in the surgery.

I wonder how Lucia's Amah coped with the immediate distress of looking after a baby and taking her home to break the news to Granny, who would have been home by herself. What confusion must have ensued for my devastated family.

|

In 1937, the procedure following a death meant that Lucy had to be buried on the day she died. My father and aunts would have been at work that day, and would have had to come home and under great pressure, organise a burial. They must have felt betrayed by God as they asked many unanswerable questions. I have understood it differently: Fate decides what happens or doesn't happen to each of us, and my God is there to hold us tight as we pick up our broken hearts and shattered lives and continue our Journeys.

Lucy's small headstone simply states her name and age and the date she died. It doesn't mention she was adored by her babies, adored by her childhood friend and husband and his loving family. In the following weeks, it is obvious my poor father's focus was not on the headstone. Although I'm seventy-three years old, the warmth of Lucy's love sits with me still, as does her jewellery and although I don't have any memory of the months that followed, her story is carved into my heart forever. An aside: Thirty years ago, I brought the small headstone home from Bidadari Cemetery and created another loving headstone for her Spirit. When Bidadari closed a few years ago, I spent a day in a picnic setting witnessing the smashing of headstones and the digging up of five family graves. A department of the British Government gave a female member of their staff to witness the digging of these graves. The graves were of Lucy, my Grandmother Annie, her husband Charles, their baby, Norman and Granny's uncle, William Allen. Fortunately, there were no bones to bring home, just a few of Lucy's teeth, the top of Granny's stocking and a bit of baby Normans white coffin. Life has certainly presented me with some challenges, which I am happy to say I have passed with full colours. We are all helpless when it comes to resisting Fate as I was to find out myself, when my perfect baby son became brain damaged at two months of age I was twenty-three! |

My Childhood

My memories are from the age of three.

The year after Lucy died had been a very difficult year for us all. Outwardly, I became a happy little girl but the emptiness persisted and persists. On the first anniversary of her death, the trunks in which Lucy's clothes had been packed away were brought outside and aired on covers, maybe sheets, to be later given away. I remember looking in all those trunks probably confused as to what it all meant and probably hoping my Lucy was in there somewhere.

After the very sad start to our lives, our family gradually became happier. I believe being around Lucia and me created a distraction for them. I have always felt we were adored. I spent most of my day with my amah, Ah Kan, who literally became my mother, as the word Amah implies. After my father and his siblings grew up, Ah Kahn had stayed on as companion to my Grandmother, so she was there to welcome me when Lucy brought me home.

I imagine before the Japanese took it all away, the children of all European families living in Singapore from 1935 to 1942, were very fortunate to have lived an idyllic childhood although problems with health would have been a major issue for our parents. My young uncle was only 18 months old when he died of diarrhoea complications. We lived a simple life in Upper East Coast Road. The back of our home faced a huge, flattish cliff face on top of which I believe, sat the "American Club." The large bungalow we lived in sat high off the ground, facing the sea. Partly surrounding our home was a wide veranda, enhanced by a beautifully moulded exterior roof made from grasses. The wide front steps led to a sandy expanse bereft of flowers or lawn but surrounded by gracefully, curved coconut palms endowed with pale, green coconuts which were so cooling to look at and smooth to touch and enjoyable to drink from.

At the end of the sand, was the seawall. It fell about fifteen feet down to the seabed and in the morning the tide disappeared leaving a pale, grey beach, strewn with startling white shells and tiny red crabs scurrying out of tiny holes...and so began my passion of collecting shells.

From a very young age, I was curious about the house next door for it had a round pool in the back in which no one swam in. In the evening when the tide came in through a cement pipe to the pool, it brought with it an assortment of fish, providing the cook with the evening's dinner. I went there many times with my amah to have a look and returned with a fish or two.

An aside: On a visit to Singapore in the '60s, I insisted my husband come with me to find my old home. We drove along East Coast Road past Bedok, where the shark-fin fishermen used to hang the fins out to dry but I couldn't find the landmark of the huge cliff wall, for the hill had been bulldozed!

Undeterred, we went back the following day and walked along a reclaimed beach, my husband carrying my sandals and handbag as driven by excitement, I powered on in front of him looking for the front of our home and the sea wall. The wall would indicate the front of my garden, or where it used to be if it was no longer there. The wall was there but the house had gone...all that was left of what I remembered, were the tiles that went from the house to the outside-kitchen. The coconut palms were still there, pale green and graceful as ever, the house next-door was still there but the family weren't. Soon a Chinese man walking along the beach came over to have a look at the strange sight of two shoe-less tourists walking around the empty property... the woman crying. After a wonderful conversation with this stranger about what I remembered, he was able to validate that the memories I had were true! I was impossibly thrilled. He was an orchid grower who now lived next door to the home with the pond!

As I write, so do I cry. I can still see myself standing in the empty space of where our home used to be. It was awful.

Our clothing in the late '30s were rompers for day wear, and very pretty dresses made of beautiful, almost weightless, soft materials, for outings, no bonnets or hats! One such dress was pink with little capped sleeves and flocked in white. Another in a French- blue type of crepe de chine, was 'smocked' on the bodice and tied up on the shoulders in a soft bow. I love looking at the photos of those dresses and those of my sandals which were white and so Italian looking!

My memories are from the age of three.

The year after Lucy died had been a very difficult year for us all. Outwardly, I became a happy little girl but the emptiness persisted and persists. On the first anniversary of her death, the trunks in which Lucy's clothes had been packed away were brought outside and aired on covers, maybe sheets, to be later given away. I remember looking in all those trunks probably confused as to what it all meant and probably hoping my Lucy was in there somewhere.

After the very sad start to our lives, our family gradually became happier. I believe being around Lucia and me created a distraction for them. I have always felt we were adored. I spent most of my day with my amah, Ah Kan, who literally became my mother, as the word Amah implies. After my father and his siblings grew up, Ah Kahn had stayed on as companion to my Grandmother, so she was there to welcome me when Lucy brought me home.

I imagine before the Japanese took it all away, the children of all European families living in Singapore from 1935 to 1942, were very fortunate to have lived an idyllic childhood although problems with health would have been a major issue for our parents. My young uncle was only 18 months old when he died of diarrhoea complications. We lived a simple life in Upper East Coast Road. The back of our home faced a huge, flattish cliff face on top of which I believe, sat the "American Club." The large bungalow we lived in sat high off the ground, facing the sea. Partly surrounding our home was a wide veranda, enhanced by a beautifully moulded exterior roof made from grasses. The wide front steps led to a sandy expanse bereft of flowers or lawn but surrounded by gracefully, curved coconut palms endowed with pale, green coconuts which were so cooling to look at and smooth to touch and enjoyable to drink from.

At the end of the sand, was the seawall. It fell about fifteen feet down to the seabed and in the morning the tide disappeared leaving a pale, grey beach, strewn with startling white shells and tiny red crabs scurrying out of tiny holes...and so began my passion of collecting shells.

From a very young age, I was curious about the house next door for it had a round pool in the back in which no one swam in. In the evening when the tide came in through a cement pipe to the pool, it brought with it an assortment of fish, providing the cook with the evening's dinner. I went there many times with my amah to have a look and returned with a fish or two.

An aside: On a visit to Singapore in the '60s, I insisted my husband come with me to find my old home. We drove along East Coast Road past Bedok, where the shark-fin fishermen used to hang the fins out to dry but I couldn't find the landmark of the huge cliff wall, for the hill had been bulldozed!

Undeterred, we went back the following day and walked along a reclaimed beach, my husband carrying my sandals and handbag as driven by excitement, I powered on in front of him looking for the front of our home and the sea wall. The wall would indicate the front of my garden, or where it used to be if it was no longer there. The wall was there but the house had gone...all that was left of what I remembered, were the tiles that went from the house to the outside-kitchen. The coconut palms were still there, pale green and graceful as ever, the house next-door was still there but the family weren't. Soon a Chinese man walking along the beach came over to have a look at the strange sight of two shoe-less tourists walking around the empty property... the woman crying. After a wonderful conversation with this stranger about what I remembered, he was able to validate that the memories I had were true! I was impossibly thrilled. He was an orchid grower who now lived next door to the home with the pond!

As I write, so do I cry. I can still see myself standing in the empty space of where our home used to be. It was awful.

Our clothing in the late '30s were rompers for day wear, and very pretty dresses made of beautiful, almost weightless, soft materials, for outings, no bonnets or hats! One such dress was pink with little capped sleeves and flocked in white. Another in a French- blue type of crepe de chine, was 'smocked' on the bodice and tied up on the shoulders in a soft bow. I love looking at the photos of those dresses and those of my sandals which were white and so Italian looking!

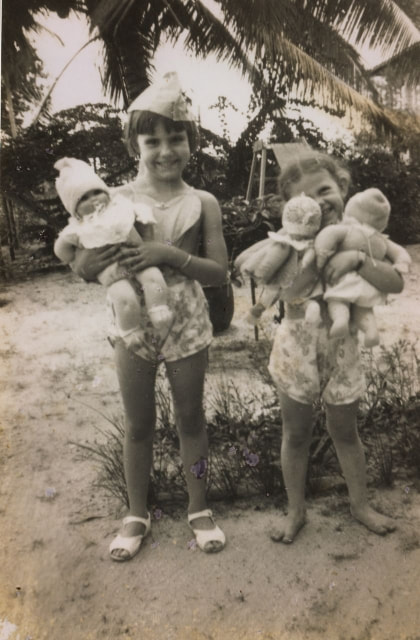

I don't remember Lucia and I playing together until she was about three years of age. When we weren't with our Amahs, we were playing in our corner of the sitting room. Our toys were quite simple as toys were in those days but I wonder why we didn't have tricycles. We had child-size cane chairs and a table where we played tea parties. We sipped 'tea' out of beautiful little Chinese cups and propped up beside us were our most amazing dolls which had little fat arms and legs, partly filled with sand, as were their bodies, and had gorgeous, appealing faces. We dressed and undressed our cut-out dolls and I spent many hours during my childhood, with my story books, wonderful coloured pencils and colouring-in books.

Although I loved playing in the corner, my favourite 'toys' were our dog Towser, a mixed breed of dog that Australians would have called a 'Heinz' dog, one with 57 varieties in him and my pet monkey, a pale golden Gibbon. He had the cutest face with rosettes of hair around his eyes, making them look huge, while his long floppy arms usually hung around my neck, Towser along side. For some reason I have always referred to the Gibbon as a Wa Wa.

My other joys were listening to the radio, singing the English Music Hall songs of 20s'/30s to my Granny and remember her playing the wind-up gramophone through the day with the lyrical music of Italian and German Tenors, and Italian operas floating through the house.

When I wasn't going somewhere on the back of Ah Khan my Amah, I spent time with people who loved me, such as the Tamil gardener and Chinese cook. It was a blessing to have Ah Khan in my life. She was not tall and had a beautiful round face. She wore her traditional white top and black pants, with her long black, plait hanging down her back. I loved that plait and when on her back, I would scrunch it up in my small hands. Aunty Clare told me that I used to love biting Ah Khan's plump, little shoulders. Ah Khan never complained. She carried me around for far longer than was necessary. We regularly visited the Victorian-styled wet market, now called Lao Pasat, went to a special place to hear caged birds singing, visited the Buddhist temples and the Death House in Sago Lane. > Ah Kan obviously had a relative living out their last days there.

Situated inside the huge hall in the Death House were elevated sections of planks. The sick and the dying lay on woven mats on these planks amid the sounds of crashing symbols. They truly alarmed me! I wonder how the sick coped with the noise. At the end of this hall, bathed in a haze of pungent incense, was an enormous Buddha. An indelible memory.

At home, Lucia and I ate local food, such as steamed rice, fish, chicken and greens, and fruit, sago and tapioca pudding. I don't remember peas, carrots, potato, or eating satay. Ah Kan and I also ate yummy street food such as Apom, a yummy Malay pancake and Quay Tu Tu, a white, light, little cake, sitting on small squares of pristine, white cotton, and steamed over glowing coals > they were filled with ground peanuts and soft, brown palm sugar, called Gula Malacca, and tasted absolutely divine. The smell of the sticky rice is still the same, the silky textured Char Sui Bao is still the same and then there are all the preserved fruits called Kanas, orange-peel plums, salty plums, tamarind rolled in sugar. Do any of you share these memories with me?

A regular visitor to my Granny in East Coast Rd was Mr C.K.Tang of "Tangs" Department Store in Orchard Rd. He began his business by delivering Chinese linen to various homes, one of which was ours. Later he rented a small part of a shop, then a larger part of the shop until he bought the shop! Later still, he built 'Tangs' as we know it, in Orchard Road.

During the time I remember, CK rode a bicycle or tricycle, and at the back he pulled a small contraption that held his tin trunk full of exquisite linen > he always brought me a bag of sweets.

Many years later, as an adult on my first visit to Singapore, I rang C.K.Tangs office could I meet CK for morning tea > C.K. agreed and so began a lovely Ritual on my future journeys to Singapore. C.K was a tall, well built man. I don't remember ever seeing such a tall, well-built Chinese man in Singapore. He spoke no English so we communicated through his nephew, Mr Wee Hee Tang. We always talked about the past, especially the massacre of local Chinese men on the beach on Beach Rd during the Occupation. His plans for the future included buying old cinemas and turning them into Churches. We sipped fragrant tea from beautiful eggshell china cups accompanied with Swiss biscuits, sent from Switzerland by one of his children. On our first meeting he said he remembered my grandmother and giving the little girl a bag of sweets, and I told him, I remembered his tin trunk filled with beautiful linen. Within a second, the old trunk appeared.

I can't explain why, but for a few moments while looking into that tin trunk, I became the little girl again. While CK remained in charge of Tangs, new employees were shown the tin box, a metaphor I felt, that said, "Work hard and you too can have what I have."

Until he died, we told stories and shared tea and cake whenever I visited Singapore. After C.K's death I was given a small replica of the trunk as a memento. I am sure somewhere in your cupboard, is some beautiful Chinese linen.

Another favourite visitor of mine to our home was a Chinese man I called the 'Ting Ting' man. I called him that because he used to ring his bicycle bell many times to alert the five year old me, that he was waiting at the back of the house to give me one of his shaved ice balls, covered in red syrup. He had been told and I had been told, I mustn't eat those ice balls because of the hopeless hygiene standards involved in the making of them. He needed two hands to make a shaved-ice ball, unfortunately, one needs one's hand to wipe one's bottom, and if one doesn't have a hanky, the other hand is needed to blow one's nose! Obviously, I didn't care enough to do the maths!

Before he joined the Australian Air Force, my darling father fashioned a long shaving blade on a 'something' to make sure we continued to have our shaved ice-balls, covered in red cordial. The ice-balls were to be another strange 'thing' those folk from Singapore ate. My young friends we very happy little suckers!

Another memory is going with my aunts Clare Edwards and Marguerite Carruthers to a theatre with a domed ceiling that in the evening opened, allowing birds to fly in and out of the theatre during the concerts. Does anyone remember that Theatre? Maybe it was the "Cathay"?

My youngest aunt Clare went to a tap-dancing school and from the age of four to nearly seven, I attended classes with her. Once a year a benefit concert was given by the School n the Raffles Hotel. The 'big girls' danced and sometimes we imitated the theme. I can 'see' the band playing on the raised Art Deco-style stage and have a photo of my class dressed as Clowns. I always thought I was the happy little girl sitting in the front row: not so. I was the child on the end of the back row on the right of the photo, with a "not amused' look on my face and I can't imagine why. I also have memories of long destroyed photos of my aunt showing the 'big' girls dancing in the shortest of shorts! They were gorgeous girls.

Too soon, events never experienced before warned us of imminent changes in our lives. For example, outside our home one morning, we watched in awe as being pulled out of the drain, was an armoured car. On another morning, a small plane went down on the huge stretch of beach in front of our home. Fortunately for the pilot, the tide was out.

Before the 'end' of my life in Singapore as I knew it, an occasional Naval mine would lose its moorings and from our sea wall when the tide went out, the mine could be clearly seen, sitting in the sand. During the retrieving of the mines, we had to leave the house. These experiences combined with the smoke and the sound of the bombs, was a sure sign for me that my childhood had ended.

Our Family's Escape from Singapore

My memories are still as fresh as milk spilt a moment ago. At home, Dad, Granny and my aunt Clare went about quietly doing what they had to do, I presume so as not to alarm Lucia and me, although I did wonder why they spent a lot of their time bandaging and unbandaging me. Later I realized they were practising First Aid from a St. John's First manual. Much later I became a St. John's Ambulance roadside nurse, a volunteer job I did for seven years.

We lived in Upper East Coast Road, not far from Changi. Living that far out of the city had spared me the sights, smells and chaos of our bombed city but only for a few weeks. Even though I could hear the bombing, and saw the huge plumes of smoke from the Shell Oil and the British Naval base, I wasn't alarmed until I awoke one morning to a cacophony of sounds in our usual empty garden. Standing on our verandah, we couldn't believe what we were seeing. For there in our once, quiet garden was a large group of very happy men. Their shirts were off showing bare, white-chests, their skinny legs covered in long baggy shorts, wearing boots and socks and on their heads were hats we had never seen. They seemed to be laughing, shouting, whistling and singing, all at once. They were Australian soldiers > the epitome of warmth and friendliness, hugging Lucia and me, when we joined them > I loved them instantly.

The soldiers were there to place a massive piece of artillery in the garden, and cover the property with barbed wire. Although I knew what a gun looked like, I had no concept of what this shape was until much later. Nevertheless, I instinctively knew it was threatening. Those joyous boys didn't realise that too soon, some of them would be killed and others endure a terrible captivity.

Within days we left Upper East Coast Road to live in the city but before we left, my father with the assistance of the gardener, dug a hole deep enough to hide household goods. He buried large, beautiful Chinese cloisonné urns, Satsuma-ware they had brought back on their honeymoon from Japan, beautiful silver cutlery and silver trophies he had received in his teens and twenties, for shooting and other sporting events...even old photos.

An aside: After the War ended, on the way back from an Air Force task in Borneo, my father returned to Singapore and found our home still standing so he was able to dig up the treasure, He shipped what he could, back home to Western Australia in tea-chests. The story at the time was the Japanese had occupied our house but hadn't discovered the treasure! The delivery of the tea chests filled our home with a much-needed sense of beauty and excitement but we were in an incongruous situation. We were poor like everyone else and had no use for crystal rose-bowls and wine glasses or silver trays, so we raved about the beauty of various pieces then repacked them and put the tea chests in the shed. The photos hadn't suffered any damage. A few years later my father died and although our treasure was sold to pay for various expenses, I managed to save a trophy tankard and as mentioned, a few spoons engraved with S.V.C S.R.V.C. My father started off with winning tea-spoons but progressed to large crystal Rose Bowls and large silver chalices. These Volunteers met regularly as Army Reserves, sharing friendships and competed with each other for various trophies in their shoot-outs. Sometime before the big change, I believe the Singapore Volunteer Corp must have split into various groups, for my father belonged to the Fortress Engineer Volunteers in those last months.

Weeks before the Surrender.

We left our seaside home to stay with my aunt and uncle, Marguerite and Andrew Carruthers in the city. We had two weeks with them before they left on a ship bound for Australia. New experiences for me were watching my father hurriedly create a shelter from tables and mattresses and witnessing a shell fly straight over the house making a screeching, whistling sound until it hit something and blew up. While there I also witnessed one of the many cruelties carried out by the Japanese. They had a neat trick of duping children and adults with small, colourful parachutes, drifting from the skies with a toy attached. Any attempt to detach the toy would have resulted in an explosion causing unimaginable trauma and quite possibly death. On a couple of occasions, we watched my father blow up the toys with a very long bamboo pole.

Although Marguerite and Andrew had left Singapore earlier, it hadn't meant they were safe. Their ship was bombed near Banka Island, just off the coast of Sumatra. Marguerite and Andrew and others who survived the sinking and reached Banka Island, were soon captured and interned. Sometime later they were transferred to a large camp in Palembang in the southern part of Sumatra > here they stayed for the rest of the War. Marguerite's camp was the camp where the women created a most amazing choir. Their story was made into a movie called "Paradise Road."

Marguerite survived the war but husband Andrew passed away a couple of months before the Japanese surrendered. Andrew had worked for the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation.

We moved to a flat in Bras Basah Road after Marguerite and Andrew left, probably because it was closest to the docks. I'm not sure how often we carried our meagre possessions over bombed roads filled with smoke and distressed people and stumbled down to the docks but it was many times. My father paid for tickets on different ships, and like many others, we waited for ships that had over-booked passages and wouldn't take us on board. On Thursday, February 12th, a P & O shipping officer told my father to bring the family down to Clifford's Pier at 3.00 p.m. Again, we waited a very long time along with many, many others for another ship that never arrived, Probably it was 'lost' on the way.

Everyone had to stay over-night because the Authorities said it was too dangerous to move women and children back

to where they had come from. My father walked back to our flat to fetch more food and water for us that we had left behind in our hurry. Time would tell how very fortunate we were to miss getting berths on any ship. Days later, unfortunate mothers and children would have been marched off to an unknown future, fearful and sad, separated from their fathers and husbands for those long and difficult years.

Friday 13th February, Two days before the Surrender.

That morning, little did anyone realise it would only be two days before the British and their Allies, surrendered to the Japanese. My father must have sensed the end was near for he decided he could no longer wait for a ship to rescue us. > He decided to take us to his sister's home on St. John's Island and hopefully to safety. It had been his plan to put our family on a ship, stay with his Volunteers and contribute to the defence of Singapore but it wasn't to be.

We waited for hours on Clifford's Pier for a barge to take us to St. John's Island. As we crossed the waters around Singapore I remember watching the city burn and listening to the sounds of War. I no longer had my beautiful mother, my Aunty Amah and now I had no home. That night I left a part of me in Singapore.

We finally arrived on St. John's Island late that night, and stayed three nights. By the third night Singapore was in the hands of the Japanese. As soon as we arrived on the Island, the Malay staff led my father to an abandoned thirty-seven foot, RAF Patrol tender. It appeared to have various problems, one of which was a rope wrapped around the propellers.

Recently, Jonathan Moffatt brought to my attention a letter my father wrote to the Malayan Research Bureau in 1943. He began the letter with a comment that he wouldn't talk of the despair or problems endured but did say he had worked for two days and nights with little sleep, trying to repair the tender and he was still repairing it when unbeknown to him the 'Surrender' to the Japanese was being signed in Singapore at 6 p.m. It was Sunday February the 15th.

Late on Sunday night, the gardener ran to tell my father that the Japanese had landed on the other side of St John's and were looking for Europeans. We had to leave immediately. My Father had no other option but to rush us down to the jetty where the tender was moored and although it was not quite ready to leave, it had been packed with sufficient essentials such as petrol, some water, rice and sardines. As we ran down to the very long jetty, Lucia (4 ½) fell and cut her chin and began crying. My father and Uncle Walter rushed her back to the house and chloroformed her, and later stitched the wound.

My aunts, Granny and I, continued running to the jetty, and hid under it. Dad hurriedly returned with a now asleep Lucia, and handed her to Granny, while he and Walter swam under this long jetty to the moored tender. I can still see my father moving away ever so slowly through the dark water. Granny told me that at one point, Japanese soldiers walked onto the jetty and after they passed, Granny, Lucia and I were taken on the backs of wonderful Malays, swimming silently to the moored tender and somehow we climbed aboard, our aunts following behind. I can't imagine what my Grandmother was going through. She never mentioned how long we sat huddled under the jetty in terrified silence with my unconscious sister in her arms but I do remember her holding her finger up to her lips to signal I had to be quiet and quiet I was. I have no idea how I managed to keep quiet during those terrible weeks for I was such a chatty child... but quiet I was. For all those weeks Lucia and I hardly said a word, we never played, or laughed and neither did the adults.

My father, in his letter, stated that we left St. John's Island at 1.00 a.m on the 16th February, bound for Sumatra. He speaks of only having the use of one engine and one rudder. The draft on the tender enabled us to clear the minefields set around Singapore, with only inches to spare. As well, Dad picked up thirty people from the sea around Singapore, most of them injured, among them a Dr H. Stubbs, Medical Officer from Chang Win Estate, Polap, Johore. Do you know of him? Strangely enough, my father knew a Dr Reginald Gordon Stubbs from Singapore. His wife and children were interned with my aunt Marguerite in Palembang. I would very much like contact with the Stubbs family.

As we left St. John's Island to motor across to Sumatra, we had the burning coast of Singapore to guide us though the sea. My father in his letter to the Malayan Office, mentions he used a very cheap compass he had bought just hours before we left from 'Change Alley', a tiny, cheap, shoppers paradise established down a lane. This cheap compass did a great job guiding us through the sea and various Islands.

From the list I have of the small Islands we stopped at on our journey to Sumatra, it seemed we travelled during the night, and hid under mangrove vines during the day. I can remember hiding under the foliage during the day. From copies of old maps, I see we went up and down two rivers before we found the mouth of the correct river, the Indrigiri River. It was to lead us to the escape route the British and Australian military had created across Sumatra.. The route took us overland to the mountain ridge, over it by train and down to the coast to the Port of Padang. It was a mad house of activity.

On the tender, I remember drinking 'pink' water. Dad had put Permanganate of Potash into rainwater to make it drinkable, and in my aunt's 'beauty case' was the smell of Friars Balsam,a simple base of the First Aid kit we had which was also used in Perth during those days, and iodine. I also remember a jar of Ponds face cream and the smell of Solyptol soap.

Although our family suffered much stress crossing Sumatra, we hadn't really suffered in comparison to families who became sick or had been captured. I don't believe Lucia or I ever were sick or hungry or covered in bites or sores though after the War my father did suffer from malaria. For all those weeks we weren't aware that Marguerite and Andrew had begun their three years of suffering in Palembang, some miles south of us, having been captured a day or two after they left Singapore weeks earlier.

At some point, while travelling up the Indigiri River my father picked up some Australian soldiers and later gave them the tender in exchange for a letter from a senior officer. The letter they gave my father would enable us to get a passage for the seven of us on a ship when we reached the port of Padang. I have no idea what happened to those men whom my father rescued from the sea. They must have gone their own way because our family travelled by themselves. If it is possible, I would love to know how they fared.

Regarding those thirty odd people rescued by my father, I have no memory of having that many people on board, probably because most of the time Lucia and I were confined to the one and only cabin but the 'ladies' could venture out on deck. Lucia and I used an air-raid helmet for a potty, and once free of the sea and in the safety of the rivers, in the evening we sat in a net of some sort over the side of the tender while my father bathed us. He probably thought his sisters and mother would fall over-board if they did the bathing!

The kind Sumatrans shared their food with us and in the Kampongs allowed us to use their showers. I remember my father carrying his wonderful trusty parang everywhere all the way to Fremantle. After we left the tender behind, we had access to small shops in the villages across the plains of Sumatra, and we were fortunate to have some money to negotiate. At one point on the journey across to Padang we did stay with many others in what could have been a Convent or Boarding School. In the middle of a huge entry hall was a most beautiful staircase.

Hiding in the day time and walking at night became the norm. We also hitched rides and my aunt Clare said we actually caught a taxi to somewhere. After some days crossing Sumatra, to get to Padang, we caught a train in the middle of the night and went over the mountains. I can still feel the train slipping backwards as we rose higher and higher over the mountain, arriving in the early hours of the morning. The only memories I have of Padang is one of chaos.

From Padang, people caught ships to Ceylon then England via India and some went to Durban or down to Australia. It would have been a very tricky and dangerous journey for ships going south to Australia, for they had to cross the open sea near the Sunda Straits.

We reached Padang safely and without any incidents and armed with the letter from the Australians, we hoped to get a safe passage on a ship. We did. There were berths for the seven of us, on the "Zaandaam", a Dutch Cruise ship that had been converted into a Red Cross or troopship, bound for Port Tjillajap in south Java. Here more chaos reigned, then thankfully onwards without any dramas, to Fremantle, Western Australia. The crossing on the south side of the Sunda Straits had already claimed many ships on their way to Tjillajap, so it was a miracle for us to sail safely to Fremantle, completely with out incident.

The End of the Edwards' Clan.

From the beginning of our journey my Grandmother had insisted on bringing the family Bible with us on our journey.

On our arrival in Fremantle, the Australian Red Cross found us a house in a caring street, called Hopetown Tce, (and a Hope town it was), Shenton Park, a suburb of Perth, Western Australia. After settling us into our new home, my father joined the Royal Australian Air .Force and with his background in engineering and jungle experience, became an Officer in the RAF Intelligence.

The unfortunate Edwards women left behind in Shenton Park, were quite a useless trio, who literally couldn't "boil water" Later this phrase was to become, among Australians, a general criticism of someone who had very few skills or appeared to be helpless. I on the other hand, learnt in a flash that how you boil a kettle of water is by learning how to light the gas....Voila! I was nearly seven and it was 'written' that I would not enjoy a childhood but become a capable 'carer' of these adult women and Lucia, when she became old enough, also became a 'carer'. We washed floors and vacuumed and I made lunches etc.

I soon learnt how to peel vegetables and cook them, cook apples, boil the hell out of any vegetable and put 'meat', potatoes and carrots, into the wood oven for a specific amount of 'time'... I learnt very quickly about 'time'. Time to get up, time to go to sleep, time to get ready, time to go and time to leave. I also learnt to read....one of the most magical things that ever happened to me. Then I learnt to chop wood and could light the bath heater with the thinnest wood-chips with a quarter of a piece of newspaper, so clever was I. Then came soaping up collars and cuffs" before clothes were into the 'copper', for boiling. Nothing so foreign as the 'copper' had come into the lives Edwards' ladies. I also learnt how to make a bed and pluck a chicken and be very careful when I had to pull the guts out so as not to break the bile sack.

Clare went to work in the Navy office. Later Lucia and I had a couple of years in boarding school and when we returned, I attended school for another couple of years and worked as a short-hand typist, but continued with my second job in the home and waited for Dad to come home.

Immediately after the Japanese surrendered in September 1945 my father was sent to Labuan, where he stayed for another nine months, leaving us for almost another year, before he was discharged.... such a long time to be without him.

By the time he returned, his sister Kathleen had returned to Malaya with her husband and child...so he never saw them again. Clare had married and gone to live in the country and Granny, Dad, Lucia and I stayed together until he died. Flying Officer, Charles Patrick Edwards died peacefully in his sleep on the 15th February 1952, ten years to the day after we left St John's Island. My distraught sister Lucia found Dad, and I as the eldest child, had to dress his dead body and organise a funeral. A few weeks later, Lucia and Granny went to Malaya and Singapore respectively to live and I stayed behind and went to live in Fremantle. I was nearly seventeen and felt as though life had truly abandoned me but even at that young age, I was fortunate to be wise enough to let go the 'things' I couldn't change and change the things I could, as St Francis of Assisi wrote a very long time ago.

Although I loved playing in the corner, my favourite 'toys' were our dog Towser, a mixed breed of dog that Australians would have called a 'Heinz' dog, one with 57 varieties in him and my pet monkey, a pale golden Gibbon. He had the cutest face with rosettes of hair around his eyes, making them look huge, while his long floppy arms usually hung around my neck, Towser along side. For some reason I have always referred to the Gibbon as a Wa Wa.

My other joys were listening to the radio, singing the English Music Hall songs of 20s'/30s to my Granny and remember her playing the wind-up gramophone through the day with the lyrical music of Italian and German Tenors, and Italian operas floating through the house.

When I wasn't going somewhere on the back of Ah Khan my Amah, I spent time with people who loved me, such as the Tamil gardener and Chinese cook. It was a blessing to have Ah Khan in my life. She was not tall and had a beautiful round face. She wore her traditional white top and black pants, with her long black, plait hanging down her back. I loved that plait and when on her back, I would scrunch it up in my small hands. Aunty Clare told me that I used to love biting Ah Khan's plump, little shoulders. Ah Khan never complained. She carried me around for far longer than was necessary. We regularly visited the Victorian-styled wet market, now called Lao Pasat, went to a special place to hear caged birds singing, visited the Buddhist temples and the Death House in Sago Lane. > Ah Kan obviously had a relative living out their last days there.

Situated inside the huge hall in the Death House were elevated sections of planks. The sick and the dying lay on woven mats on these planks amid the sounds of crashing symbols. They truly alarmed me! I wonder how the sick coped with the noise. At the end of this hall, bathed in a haze of pungent incense, was an enormous Buddha. An indelible memory.

At home, Lucia and I ate local food, such as steamed rice, fish, chicken and greens, and fruit, sago and tapioca pudding. I don't remember peas, carrots, potato, or eating satay. Ah Kan and I also ate yummy street food such as Apom, a yummy Malay pancake and Quay Tu Tu, a white, light, little cake, sitting on small squares of pristine, white cotton, and steamed over glowing coals > they were filled with ground peanuts and soft, brown palm sugar, called Gula Malacca, and tasted absolutely divine. The smell of the sticky rice is still the same, the silky textured Char Sui Bao is still the same and then there are all the preserved fruits called Kanas, orange-peel plums, salty plums, tamarind rolled in sugar. Do any of you share these memories with me?

A regular visitor to my Granny in East Coast Rd was Mr C.K.Tang of "Tangs" Department Store in Orchard Rd. He began his business by delivering Chinese linen to various homes, one of which was ours. Later he rented a small part of a shop, then a larger part of the shop until he bought the shop! Later still, he built 'Tangs' as we know it, in Orchard Road.

During the time I remember, CK rode a bicycle or tricycle, and at the back he pulled a small contraption that held his tin trunk full of exquisite linen > he always brought me a bag of sweets.

Many years later, as an adult on my first visit to Singapore, I rang C.K.Tangs office could I meet CK for morning tea > C.K. agreed and so began a lovely Ritual on my future journeys to Singapore. C.K was a tall, well built man. I don't remember ever seeing such a tall, well-built Chinese man in Singapore. He spoke no English so we communicated through his nephew, Mr Wee Hee Tang. We always talked about the past, especially the massacre of local Chinese men on the beach on Beach Rd during the Occupation. His plans for the future included buying old cinemas and turning them into Churches. We sipped fragrant tea from beautiful eggshell china cups accompanied with Swiss biscuits, sent from Switzerland by one of his children. On our first meeting he said he remembered my grandmother and giving the little girl a bag of sweets, and I told him, I remembered his tin trunk filled with beautiful linen. Within a second, the old trunk appeared.

I can't explain why, but for a few moments while looking into that tin trunk, I became the little girl again. While CK remained in charge of Tangs, new employees were shown the tin box, a metaphor I felt, that said, "Work hard and you too can have what I have."

Until he died, we told stories and shared tea and cake whenever I visited Singapore. After C.K's death I was given a small replica of the trunk as a memento. I am sure somewhere in your cupboard, is some beautiful Chinese linen.

Another favourite visitor of mine to our home was a Chinese man I called the 'Ting Ting' man. I called him that because he used to ring his bicycle bell many times to alert the five year old me, that he was waiting at the back of the house to give me one of his shaved ice balls, covered in red syrup. He had been told and I had been told, I mustn't eat those ice balls because of the hopeless hygiene standards involved in the making of them. He needed two hands to make a shaved-ice ball, unfortunately, one needs one's hand to wipe one's bottom, and if one doesn't have a hanky, the other hand is needed to blow one's nose! Obviously, I didn't care enough to do the maths!

Before he joined the Australian Air Force, my darling father fashioned a long shaving blade on a 'something' to make sure we continued to have our shaved ice-balls, covered in red cordial. The ice-balls were to be another strange 'thing' those folk from Singapore ate. My young friends we very happy little suckers!

Another memory is going with my aunts Clare Edwards and Marguerite Carruthers to a theatre with a domed ceiling that in the evening opened, allowing birds to fly in and out of the theatre during the concerts. Does anyone remember that Theatre? Maybe it was the "Cathay"?

My youngest aunt Clare went to a tap-dancing school and from the age of four to nearly seven, I attended classes with her. Once a year a benefit concert was given by the School n the Raffles Hotel. The 'big girls' danced and sometimes we imitated the theme. I can 'see' the band playing on the raised Art Deco-style stage and have a photo of my class dressed as Clowns. I always thought I was the happy little girl sitting in the front row: not so. I was the child on the end of the back row on the right of the photo, with a "not amused' look on my face and I can't imagine why. I also have memories of long destroyed photos of my aunt showing the 'big' girls dancing in the shortest of shorts! They were gorgeous girls.

Too soon, events never experienced before warned us of imminent changes in our lives. For example, outside our home one morning, we watched in awe as being pulled out of the drain, was an armoured car. On another morning, a small plane went down on the huge stretch of beach in front of our home. Fortunately for the pilot, the tide was out.

Before the 'end' of my life in Singapore as I knew it, an occasional Naval mine would lose its moorings and from our sea wall when the tide went out, the mine could be clearly seen, sitting in the sand. During the retrieving of the mines, we had to leave the house. These experiences combined with the smoke and the sound of the bombs, was a sure sign for me that my childhood had ended.

Our Family's Escape from Singapore

My memories are still as fresh as milk spilt a moment ago. At home, Dad, Granny and my aunt Clare went about quietly doing what they had to do, I presume so as not to alarm Lucia and me, although I did wonder why they spent a lot of their time bandaging and unbandaging me. Later I realized they were practising First Aid from a St. John's First manual. Much later I became a St. John's Ambulance roadside nurse, a volunteer job I did for seven years.

We lived in Upper East Coast Road, not far from Changi. Living that far out of the city had spared me the sights, smells and chaos of our bombed city but only for a few weeks. Even though I could hear the bombing, and saw the huge plumes of smoke from the Shell Oil and the British Naval base, I wasn't alarmed until I awoke one morning to a cacophony of sounds in our usual empty garden. Standing on our verandah, we couldn't believe what we were seeing. For there in our once, quiet garden was a large group of very happy men. Their shirts were off showing bare, white-chests, their skinny legs covered in long baggy shorts, wearing boots and socks and on their heads were hats we had never seen. They seemed to be laughing, shouting, whistling and singing, all at once. They were Australian soldiers > the epitome of warmth and friendliness, hugging Lucia and me, when we joined them > I loved them instantly.

The soldiers were there to place a massive piece of artillery in the garden, and cover the property with barbed wire. Although I knew what a gun looked like, I had no concept of what this shape was until much later. Nevertheless, I instinctively knew it was threatening. Those joyous boys didn't realise that too soon, some of them would be killed and others endure a terrible captivity.

Within days we left Upper East Coast Road to live in the city but before we left, my father with the assistance of the gardener, dug a hole deep enough to hide household goods. He buried large, beautiful Chinese cloisonné urns, Satsuma-ware they had brought back on their honeymoon from Japan, beautiful silver cutlery and silver trophies he had received in his teens and twenties, for shooting and other sporting events...even old photos.

An aside: After the War ended, on the way back from an Air Force task in Borneo, my father returned to Singapore and found our home still standing so he was able to dig up the treasure, He shipped what he could, back home to Western Australia in tea-chests. The story at the time was the Japanese had occupied our house but hadn't discovered the treasure! The delivery of the tea chests filled our home with a much-needed sense of beauty and excitement but we were in an incongruous situation. We were poor like everyone else and had no use for crystal rose-bowls and wine glasses or silver trays, so we raved about the beauty of various pieces then repacked them and put the tea chests in the shed. The photos hadn't suffered any damage. A few years later my father died and although our treasure was sold to pay for various expenses, I managed to save a trophy tankard and as mentioned, a few spoons engraved with S.V.C S.R.V.C. My father started off with winning tea-spoons but progressed to large crystal Rose Bowls and large silver chalices. These Volunteers met regularly as Army Reserves, sharing friendships and competed with each other for various trophies in their shoot-outs. Sometime before the big change, I believe the Singapore Volunteer Corp must have split into various groups, for my father belonged to the Fortress Engineer Volunteers in those last months.

Weeks before the Surrender.

We left our seaside home to stay with my aunt and uncle, Marguerite and Andrew Carruthers in the city. We had two weeks with them before they left on a ship bound for Australia. New experiences for me were watching my father hurriedly create a shelter from tables and mattresses and witnessing a shell fly straight over the house making a screeching, whistling sound until it hit something and blew up. While there I also witnessed one of the many cruelties carried out by the Japanese. They had a neat trick of duping children and adults with small, colourful parachutes, drifting from the skies with a toy attached. Any attempt to detach the toy would have resulted in an explosion causing unimaginable trauma and quite possibly death. On a couple of occasions, we watched my father blow up the toys with a very long bamboo pole.

Although Marguerite and Andrew had left Singapore earlier, it hadn't meant they were safe. Their ship was bombed near Banka Island, just off the coast of Sumatra. Marguerite and Andrew and others who survived the sinking and reached Banka Island, were soon captured and interned. Sometime later they were transferred to a large camp in Palembang in the southern part of Sumatra > here they stayed for the rest of the War. Marguerite's camp was the camp where the women created a most amazing choir. Their story was made into a movie called "Paradise Road."

Marguerite survived the war but husband Andrew passed away a couple of months before the Japanese surrendered. Andrew had worked for the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation.

We moved to a flat in Bras Basah Road after Marguerite and Andrew left, probably because it was closest to the docks. I'm not sure how often we carried our meagre possessions over bombed roads filled with smoke and distressed people and stumbled down to the docks but it was many times. My father paid for tickets on different ships, and like many others, we waited for ships that had over-booked passages and wouldn't take us on board. On Thursday, February 12th, a P & O shipping officer told my father to bring the family down to Clifford's Pier at 3.00 p.m. Again, we waited a very long time along with many, many others for another ship that never arrived, Probably it was 'lost' on the way.

Everyone had to stay over-night because the Authorities said it was too dangerous to move women and children back

to where they had come from. My father walked back to our flat to fetch more food and water for us that we had left behind in our hurry. Time would tell how very fortunate we were to miss getting berths on any ship. Days later, unfortunate mothers and children would have been marched off to an unknown future, fearful and sad, separated from their fathers and husbands for those long and difficult years.

Friday 13th February, Two days before the Surrender.

That morning, little did anyone realise it would only be two days before the British and their Allies, surrendered to the Japanese. My father must have sensed the end was near for he decided he could no longer wait for a ship to rescue us. > He decided to take us to his sister's home on St. John's Island and hopefully to safety. It had been his plan to put our family on a ship, stay with his Volunteers and contribute to the defence of Singapore but it wasn't to be.

We waited for hours on Clifford's Pier for a barge to take us to St. John's Island. As we crossed the waters around Singapore I remember watching the city burn and listening to the sounds of War. I no longer had my beautiful mother, my Aunty Amah and now I had no home. That night I left a part of me in Singapore.

We finally arrived on St. John's Island late that night, and stayed three nights. By the third night Singapore was in the hands of the Japanese. As soon as we arrived on the Island, the Malay staff led my father to an abandoned thirty-seven foot, RAF Patrol tender. It appeared to have various problems, one of which was a rope wrapped around the propellers.

Recently, Jonathan Moffatt brought to my attention a letter my father wrote to the Malayan Research Bureau in 1943. He began the letter with a comment that he wouldn't talk of the despair or problems endured but did say he had worked for two days and nights with little sleep, trying to repair the tender and he was still repairing it when unbeknown to him the 'Surrender' to the Japanese was being signed in Singapore at 6 p.m. It was Sunday February the 15th.

Late on Sunday night, the gardener ran to tell my father that the Japanese had landed on the other side of St John's and were looking for Europeans. We had to leave immediately. My Father had no other option but to rush us down to the jetty where the tender was moored and although it was not quite ready to leave, it had been packed with sufficient essentials such as petrol, some water, rice and sardines. As we ran down to the very long jetty, Lucia (4 ½) fell and cut her chin and began crying. My father and Uncle Walter rushed her back to the house and chloroformed her, and later stitched the wound.

My aunts, Granny and I, continued running to the jetty, and hid under it. Dad hurriedly returned with a now asleep Lucia, and handed her to Granny, while he and Walter swam under this long jetty to the moored tender. I can still see my father moving away ever so slowly through the dark water. Granny told me that at one point, Japanese soldiers walked onto the jetty and after they passed, Granny, Lucia and I were taken on the backs of wonderful Malays, swimming silently to the moored tender and somehow we climbed aboard, our aunts following behind. I can't imagine what my Grandmother was going through. She never mentioned how long we sat huddled under the jetty in terrified silence with my unconscious sister in her arms but I do remember her holding her finger up to her lips to signal I had to be quiet and quiet I was. I have no idea how I managed to keep quiet during those terrible weeks for I was such a chatty child... but quiet I was. For all those weeks Lucia and I hardly said a word, we never played, or laughed and neither did the adults.