Changi Child by Bill Kirwan

Before, During and After - A Very Different Life

History

William Burrows Senior, his wife Ann and son William Burrows II, moved to the Isle of Man, from Cumberland, England, to farm 300 acres at ‘the Creggans', an area which is now the Douglas Airport. Young William was born on the 6th July 1830. His two brothers, John and Richard Tyson were born at ‘the Creggans' on the IOM. The life of a farmer did not appeal to William who went to sea at age 17. He obtained his Mates Certificate when 21 and worked on many ships going to the Far East. He captained a number of ships and travelled to Borneo (Kalimantan), the Celebes (Sulawesi), China, India and Java, and in September 1854, records show he transported 200 convicts in good health and with no loss of life to Fremantle, Western Australia on the ‘Runnymede'.

Captain William Burrows was given a charter to clear the Malayan Archipelago of pirates who were disrupting the shipping trade. The main problem in the Malacca Straits were the Bugi pirates off Sumatra (there were Indonesian and Boyanese pirates operating in the area as well). These pirates were to extract a savage revenge later, when forced to leave the area. They killed 2 of his young children. One child was decapitated, with his head and body found on different sides of Sentosa Island.

Burrows and his friend, James Brooke, put down a revolt in Borneo and the Sultan of Johore presented the area of Sarawak to Brooke in appreciation. He was the first of a dynasty of three ‘White Rajs' to rule Sarawak for 100 years. Captain Burrows used his 2 gun schooner ‘The Royalist' in restoring order and I believe this is where he met his wife Mona, a Malay Princess, referred to in letters as the Dyak Lady. Most people from Northern Borneo were referred to as Dyak although the name really referred to the jungle headhunters of that large island.

William Burrows Senior, his wife Ann and son William Burrows II, moved to the Isle of Man, from Cumberland, England, to farm 300 acres at ‘the Creggans', an area which is now the Douglas Airport. Young William was born on the 6th July 1830. His two brothers, John and Richard Tyson were born at ‘the Creggans' on the IOM. The life of a farmer did not appeal to William who went to sea at age 17. He obtained his Mates Certificate when 21 and worked on many ships going to the Far East. He captained a number of ships and travelled to Borneo (Kalimantan), the Celebes (Sulawesi), China, India and Java, and in September 1854, records show he transported 200 convicts in good health and with no loss of life to Fremantle, Western Australia on the ‘Runnymede'.

Captain William Burrows was given a charter to clear the Malayan Archipelago of pirates who were disrupting the shipping trade. The main problem in the Malacca Straits were the Bugi pirates off Sumatra (there were Indonesian and Boyanese pirates operating in the area as well). These pirates were to extract a savage revenge later, when forced to leave the area. They killed 2 of his young children. One child was decapitated, with his head and body found on different sides of Sentosa Island.

Burrows and his friend, James Brooke, put down a revolt in Borneo and the Sultan of Johore presented the area of Sarawak to Brooke in appreciation. He was the first of a dynasty of three ‘White Rajs' to rule Sarawak for 100 years. Captain Burrows used his 2 gun schooner ‘The Royalist' in restoring order and I believe this is where he met his wife Mona, a Malay Princess, referred to in letters as the Dyak Lady. Most people from Northern Borneo were referred to as Dyak although the name really referred to the jungle headhunters of that large island.

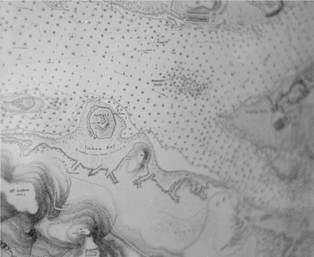

Button Island, the pylon stands on the foundations of Captain Burrows’ house. The little islet is now joined to Blakang Mati or Sentosa Island, shown in the background on the first photo and to the right in the second photo.

He became Singapore’s first Qualified Pilot and bought 2 islands. Blakang Mati, known as the Island of Death (because there was a Malay cemetery there and pirates would also leave their victims there), now called Sentosa Island and the tiny Pulau Selegu or Button Island, opposite Tanjong Pagar Harbour. Button Island is now part of Sentosa and the cable car pylon stands on the ruins of his house. He formed a Pilots Club and with 6 others, controlled all shipping in and out of Singapore and became wealthy. He was forced later to join the Harbour Board as a Civil Servant and became the first Harbourmaster of Singapore.

It is believed that he lived on his islands to protect his Eurasian children from the slights of Colonial British. He had intended to return to the Isle of Man with his unmarried children and passed Power of Attorney to his lawyer but then collapsed on the S. Devonhurst after taking her out for sea trials after repairs. He was removed to Tanjong Pagar Harbour but died at the age of 54. He had lived in the ‘land of the Dyak and the habitat of the Malay race for nearly 38 years’. The lawyer and the Captain’s money disappeared, by the time they located him in England, he too had died and the inheritance passed onto the son and out of legal reach.

It is believed that he lived on his islands to protect his Eurasian children from the slights of Colonial British. He had intended to return to the Isle of Man with his unmarried children and passed Power of Attorney to his lawyer but then collapsed on the S. Devonhurst after taking her out for sea trials after repairs. He was removed to Tanjong Pagar Harbour but died at the age of 54. He had lived in the ‘land of the Dyak and the habitat of the Malay race for nearly 38 years’. The lawyer and the Captain’s money disappeared, by the time they located him in England, he too had died and the inheritance passed onto the son and out of legal reach.

|

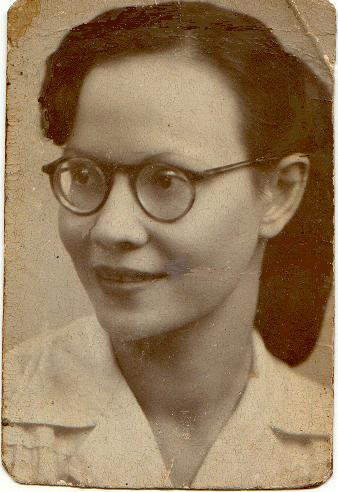

Captain Burrows’ son, born on his schooner, was named Royalist or Roy after his ship, became a ship’s Engineer and had 4 children. My mother, Gwen Eileen Burrows, was the youngest. She would refuse to answer any questions on our ancestry as I suppose she thought she was protecting her children. Parents did not talk to their children in those days and you soon stopped asking. Mum always said when asked about relatives, ‘they are few now and best forgotten’

My paternal Grandfather, William Thomas Kirwan II, left Melbourne to fight in the Maori Wars in New Zealand. He joined the 1st Waikato Regiment, married an Australian girl there from Melbourne, Margaret King, and stayed 22 years. |

My father, Herbert (Bertie) Kirwan of Irish-Australian decent, was born in Whakitane, New Zealand in 1879 and the family returned to Albury, New South Wales, Australia, after Bertie’s mother died when he was just 5 years old. Times were hard and his father had to work on a distant farm. Young Bertie was forced to work hard for a living as a farmhand when he was only 10. Mum said he was almost worked to death and earned ‘5 shillings a month and a pair of Blucher boots’ a year. He became an expert horseman and crack-shot and joined Lance Scuthorpe’s Wild West Show at the age of 14 as a breaker, trick rider and marksman. This show travelled up and down central NSW and even into Victoria and Queensland.

His favorite sister Ada’s husband, John White, got a contract to deliver 400 horses to start up horse racing in Malaya and Bertie was asked to do one trip and care for the horses. At the age of 18 years, he arrived in Singapore and stayed 50 years. He broke the horses in and started up a stock feed and saddlery business, became a Government hunter, trained polo ponies and then became a jockey and later a trainer. He was a friend of the young Sultan of Johore, a keen hunter, who helped put Bertie through night school to do his books for his business. Bertie ran a riding school and taught the Governor’s children, was welcome at Government House and was part of the Singapore social scene. He also got all the contracts to load and unload cattle sheep and horses for Burns Phillip, Dalgetty and Mansfield & Co. Bertie is mentioned in ‘Something about Horses in Malaya’, by Rene Henry De Solminhac Onraet, (1938-Kelly & Walsh, Singapore), as the ‘finest judge of pace in the country’. Mr. Onraet was a Chief Superintendent of Police. Bertie was also a Master in the Singapore Masonic Lodge. He was a top speedway motorbike rider and his son Pat was also involved in the sport.

Dad told me once while deep in the jungle, he came across the skeleton of a python still round a tree and coiled round the skeleton of a tiger. It has been a struggle to the death and he was so sorry he did not have a camera to record this rare sight. On another occasion, he had been called to a rubber plantation where an Indian tapper collecting the latex rubber from trees, was killed by a tiger. Bertie left the body as bait and made a platform 30 feet up in a tree. That night he waited but fell asleep to wake to the tree moving.

His favorite sister Ada’s husband, John White, got a contract to deliver 400 horses to start up horse racing in Malaya and Bertie was asked to do one trip and care for the horses. At the age of 18 years, he arrived in Singapore and stayed 50 years. He broke the horses in and started up a stock feed and saddlery business, became a Government hunter, trained polo ponies and then became a jockey and later a trainer. He was a friend of the young Sultan of Johore, a keen hunter, who helped put Bertie through night school to do his books for his business. Bertie ran a riding school and taught the Governor’s children, was welcome at Government House and was part of the Singapore social scene. He also got all the contracts to load and unload cattle sheep and horses for Burns Phillip, Dalgetty and Mansfield & Co. Bertie is mentioned in ‘Something about Horses in Malaya’, by Rene Henry De Solminhac Onraet, (1938-Kelly & Walsh, Singapore), as the ‘finest judge of pace in the country’. Mr. Onraet was a Chief Superintendent of Police. Bertie was also a Master in the Singapore Masonic Lodge. He was a top speedway motorbike rider and his son Pat was also involved in the sport.

Dad told me once while deep in the jungle, he came across the skeleton of a python still round a tree and coiled round the skeleton of a tiger. It has been a struggle to the death and he was so sorry he did not have a camera to record this rare sight. On another occasion, he had been called to a rubber plantation where an Indian tapper collecting the latex rubber from trees, was killed by a tiger. Bertie left the body as bait and made a platform 30 feet up in a tree. That night he waited but fell asleep to wake to the tree moving.

|

He saw 2 pairs of eyes looking at him at the same level and instantly fired some shots, hearing a crash. He stayed awake for the rest of the night and when daylight came, he found 2 tigers dead on the ground. They had stalked him up his ‘safe’ tree. Dad said he should have known better as they were, after all, big cats.

Bertie married an Australian, Ruby Batchelor, and had 2 children, Patrick and Lucy. His wife died of blood poisoning and the children were sent to his sister Fanny in Kancoona, near Dederang, in Victoria. When they returned to Singapore, Pat rode for Bertie before trying the racing in Java and returned to Malaya to work on the tin dredges. This country supplied one third of the world’s tin. These dredges were huge floating machines, which pulled up the alluvial tin from the water. When the tin ran out, these would have to be dismantled and rebuilt on the new site. Lucy married Charles Edwards, a friend and shooting mate of Bertie’s and they had 2 girls, Patricia and Lucia. Lucy also died young, on the operating table, the anesthetist was said to have been drunk. Lucy had mentioned to Mum, she knew she would die young like her mother Ruby. |

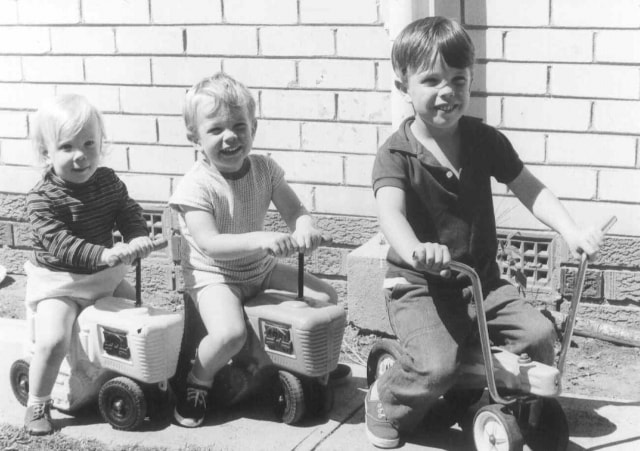

Bill ‘Winkie’ aged 3, 194

|

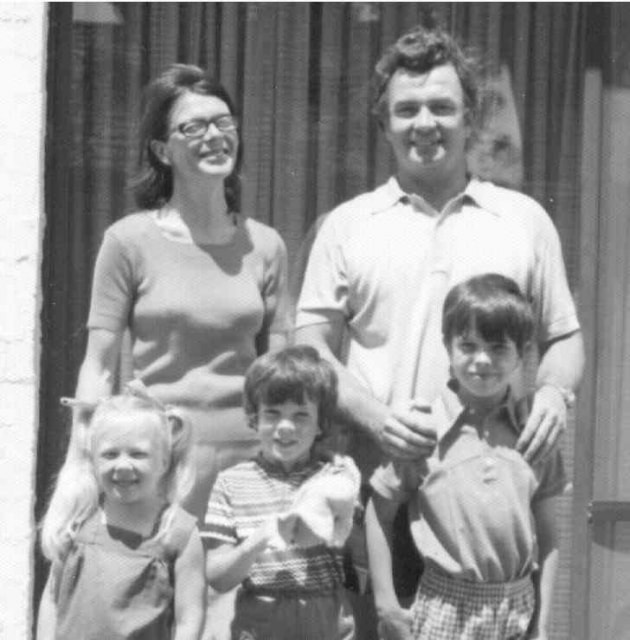

Bertie remained a widower for 20 odd years and prospered, having 3 houses and a holiday beach house way out on the water at Ponggol for entertaining horse owners and owned 22 racehorses. He married Gwen Eileen Burrows, 35 years his junior. She was the Granddaughter of Captain William Burrows and they had one son William Thomas III, born in September 1938. The Burrows islands of Button and Sentosa were requisitioned by the British for defense. They were force-purchased for a song, well below their true value. Sentosa Island is worth a fortune today as a tourist resort.

Gwen was brought up with belief in the super-natural, quite common in the East. She would tell that her family had lived in a haunted house. She said that hot stones would appear out of nowhere and fall on the carpet in their living room, even when all the windows and doors were locked. She often spoke of her mother closing doors, hearing a thud, opening the door to find a kitchen knife embedded in it. They eventually had to get a Malay Holy man to exorcise the home before they were rid of the spirits. Another thing, every New year, she insisted in both the front and back doors being open to allow the New Year in and the Old Year out, otherwise you would have bad luck. I cover my bets, I don’t disbelieve anything. Bertie was a great horseman and it is recorded that when King George V visited Singapore in 1930s, he was given the First Postillion ride on the Royal Coach. The postillion is the rider who controls each pair of horses attached to the coach, the First Postillion is the place of honour for the best horseman. There is a picture of this in the book, ‘Singapore- the first 100 years’. I have a Newspaper clipping where Bertie had a troublesome horse, very shy at the single elastic barrier used at racetracks then. Dad dismounted and when the barrier went up and the horses took off, he vaulted into the saddle and won the race. He had a 14-year-old horse called Maintain and won several races with it, quite a feat really and at great odds, due to its age. |

Chapter 1 – Changi and Sime Road Camp - 1941-1945

The British Forces were ill-prepared for the coming war. Japanese merchants and dentists travelled over Malaya marking all the jungle tracks as detours on maps for future Military use. Even when the Japanese had landed in the north, Mum and Dad joined others in celebrating Christmas and New Year in a well-lit Singapore. Defeat was not even considered a possibility. As the war grew closer and the evacuations began, the British put 3 AA guns in our front gardens and 2 trucks of ammunition under our home. There was nothing left after the war. I believe the Commanding General Percival, (some say it was the Governor), had refused to allow defenses to be built facing Malaya as it would be demoralising to the civilian population.

Bertie said the British even put machine-guns on the roof of the General Hospital and this drew the Zeros down strafing the hospital. Dad was in the Volunteer Medical Service as he was too old for Military service and his job was to clean down the operating tables. The Japanese reached the blown Causeway and cut the water supply, which came from Johore State in Malaya. Bertie said maintaining standards in the Hospital was impossible and all he could do was to wipe the blood off the tables for the next casualty. The grounds of St. Andrews Cathedral were used to bury many of the dead. I had been christened there.

My half-brother Pat, from Dad’s first marriage, had joined the Singapore Volunteer Rifles and managed to get his wife Winnie and son Herbert, away on a ship bound for Fremantle, Western Australia. But Naval actions had diverted the ship to Ceylon, India, and then Africa and they ended up in Durban, South Africa before they were allowed to land. Pat was captured in Java and sent to Kuching in Sarawak, Borneo. Dad had got us on one of the last ships leaving, the Vyner Brooke, but as he had to stay, Mum and I disembarked to be with him. Dad was very angry at the time, as we were to spend 3 and a half, long years internment under the Japanese.

However, that ship sailed and was strafed, torpedoed and sunk off Sumatra with those Australian Nurses aboard. That particular group reached shore to be met by Japanese soldiers. The men were separated, taken round a bluff and bayoneted and the women forced back into the sea and machine-gunned in the water. Sister Bullwinkel was the only survivor and managed to join another group of prisoners who kept her wounds a secret from the Japanese. She survived the war to report that crime.

Mum said that when the Japs had landed on Singapore and were closing in, and people were waiting for the end, there was a range of different behaviours. Some soldiers fought to get on ships of all sizes, others looted stores, mainly for alcohol and many sat composed, just playing cards and waited. No one nationality was better or worse than the other. Many believed that once the order to surrender was given, any restriction on them was lifted. All were bewildered and confused at this conclusion and some new British and Aussie troops even arrived in time to be captured. The Chinese were the most frightened of the local population as the Japanese had been fighting and killing the Chinese race for since 1937.

After capitulation, the victorious Japanese Army broadcast assembly points and instructions to all Allied soldiers and civilians. The Japanese assembled all Internees on the Padang or playing fields in front of the Municipal Buildings. Each person was to bring one suitcase and most did, but the clever Dutch came loaded down with many bags which enabled them to establish themselves in a better ‘financial’ position for the duration of the war. 4,700 men, women and children were imprisoned in Changi Jail, which was built to house 600. The huge Selerang Barracks complex close by, designed for 17,000 troops, held 80,000 British, Indian, Dutch and Australian prisoners.

We survived 2 years in Changi before the Japanese decided it was wiser to house troublesome soldiers than civilians in the jail and in May 1944 we were moved to Sime Road Camp, an old RAF camp, now the Singapore Country Club. Mum and I shared a hut with 30 others but we had a small area at the end separated by a ‘blanket’ curtain, which gave us some privacy. One wall had a charcoal sketch of an English orchard by Ronald Searle, who later did the drawings of the Belles of St.Trinians. There was another wall drawing of cats, in memory of those eaten. This was our home for the next one and a half years.

The British Forces were ill-prepared for the coming war. Japanese merchants and dentists travelled over Malaya marking all the jungle tracks as detours on maps for future Military use. Even when the Japanese had landed in the north, Mum and Dad joined others in celebrating Christmas and New Year in a well-lit Singapore. Defeat was not even considered a possibility. As the war grew closer and the evacuations began, the British put 3 AA guns in our front gardens and 2 trucks of ammunition under our home. There was nothing left after the war. I believe the Commanding General Percival, (some say it was the Governor), had refused to allow defenses to be built facing Malaya as it would be demoralising to the civilian population.

Bertie said the British even put machine-guns on the roof of the General Hospital and this drew the Zeros down strafing the hospital. Dad was in the Volunteer Medical Service as he was too old for Military service and his job was to clean down the operating tables. The Japanese reached the blown Causeway and cut the water supply, which came from Johore State in Malaya. Bertie said maintaining standards in the Hospital was impossible and all he could do was to wipe the blood off the tables for the next casualty. The grounds of St. Andrews Cathedral were used to bury many of the dead. I had been christened there.

My half-brother Pat, from Dad’s first marriage, had joined the Singapore Volunteer Rifles and managed to get his wife Winnie and son Herbert, away on a ship bound for Fremantle, Western Australia. But Naval actions had diverted the ship to Ceylon, India, and then Africa and they ended up in Durban, South Africa before they were allowed to land. Pat was captured in Java and sent to Kuching in Sarawak, Borneo. Dad had got us on one of the last ships leaving, the Vyner Brooke, but as he had to stay, Mum and I disembarked to be with him. Dad was very angry at the time, as we were to spend 3 and a half, long years internment under the Japanese.

However, that ship sailed and was strafed, torpedoed and sunk off Sumatra with those Australian Nurses aboard. That particular group reached shore to be met by Japanese soldiers. The men were separated, taken round a bluff and bayoneted and the women forced back into the sea and machine-gunned in the water. Sister Bullwinkel was the only survivor and managed to join another group of prisoners who kept her wounds a secret from the Japanese. She survived the war to report that crime.

Mum said that when the Japs had landed on Singapore and were closing in, and people were waiting for the end, there was a range of different behaviours. Some soldiers fought to get on ships of all sizes, others looted stores, mainly for alcohol and many sat composed, just playing cards and waited. No one nationality was better or worse than the other. Many believed that once the order to surrender was given, any restriction on them was lifted. All were bewildered and confused at this conclusion and some new British and Aussie troops even arrived in time to be captured. The Chinese were the most frightened of the local population as the Japanese had been fighting and killing the Chinese race for since 1937.

After capitulation, the victorious Japanese Army broadcast assembly points and instructions to all Allied soldiers and civilians. The Japanese assembled all Internees on the Padang or playing fields in front of the Municipal Buildings. Each person was to bring one suitcase and most did, but the clever Dutch came loaded down with many bags which enabled them to establish themselves in a better ‘financial’ position for the duration of the war. 4,700 men, women and children were imprisoned in Changi Jail, which was built to house 600. The huge Selerang Barracks complex close by, designed for 17,000 troops, held 80,000 British, Indian, Dutch and Australian prisoners.

We survived 2 years in Changi before the Japanese decided it was wiser to house troublesome soldiers than civilians in the jail and in May 1944 we were moved to Sime Road Camp, an old RAF camp, now the Singapore Country Club. Mum and I shared a hut with 30 others but we had a small area at the end separated by a ‘blanket’ curtain, which gave us some privacy. One wall had a charcoal sketch of an English orchard by Ronald Searle, who later did the drawings of the Belles of St.Trinians. There was another wall drawing of cats, in memory of those eaten. This was our home for the next one and a half years.

|

The Camp was better than Changi as it was open and movement was possible. The women, girls and young boys were in one camp and the men and older boys were held in the adjacent camp. I believe the men cooked the food in large tubs and brought it to the women’s camp. I think there was a small park and husbands and wives and children were allowed to meet every few months if the Commandant Tominaga was feeling generous. The women organised the running of their camp and held classes, grew vegetables and ran concerts.

At the start when somebody died, the coffin was taken out and buried. Later, when the war turned and wood got scarce, the body was buried and the coffin returned to the camp. The men would try to get on the burial party, as it was possible to smuggle fruit, food, some medicines and baby foods back in the empty coffin past the guard. I remember when I fell and cut my knee, I was taken to the Chapel to watch the religious paintings on the ceiling as they stitched my wound. There were people who went mad and sang to the full moon, some ate grass and others trapped rats, frogs and snails for food. Mum remembers one woman excitedly exclaiming she found a piece of meat in the soup only to discover she had a little frog, which had fallen in. |

I remember one woman playing ‘La Compasita’ and ‘Jealousy’, on her gramophone, over and over again. I suppose it was her only record. A fellow inmate, Shelia Bruin/Allen, told me years later that they learnt to tango to that record. There were shortages of everything and people were sick and dying but whatever our problems, things were worse with the POW’s. In spite of their troubles, some of the POW’s managed to make toys for the interned children.

We would hear the distinct sound of Kendo when the Japanese Officers practiced their swordplay. The clash of bamboo against bamboo, helmet and breastplates and the yells of the men would penetrate down to the huts from the guardhouse and the Commandant’s house on the hill.

Towards the end of the war, the skies were filled with Allied planes from Burma and sometimes they would drop Red Cross parcels. The Guards would fire their single AA gun and we saw the black puffs of smoke well below the planes. If any parachutes landed within the camp, we tried to hide the boxes before the Japs ran down from the guardhouse and collected them. Once we did manage to save one parcel and our whole hut of 30 shared the contents. It had Canadian Red Cross stamped on the side and we excitedly opened it. I remember the paper straw packing, the tins of meat, butter, cigarettes, and even chewing gum. Mum and I received 2 tins of Condensed Milk and for my sixth birthday, we ate a tin each. This had turned hard in the tropical heat and was like caramel and we were both very ill later.

The Japanese instructed the women to sew caps and make kidney belts for their troops and they would receive extra food for their children. Mum refused and was noted as a troublemaker. When a couple of women had affairs with Japanese Officers, Mum went up to them and said ‘this war will not last forever and you will pay’. They must have mentioned this to the officers because later when there was an inspection for hidden radios, Mum was take to the guard house, raped, then beaten with a hoe handle and baseball bat and kept there for a week. She admits she was very lucky to return.

After the war these women quickly left but Mum was a chief witness at the War Trials held in Singapore. She was instrumental in getting Commandant Tominaga, executed and was commended for her clear testimony by the Judge. Mum also said that when the commando ship the ‘Krait’ slipped into Singapore Harbour and the men of Z Force sank all that shipping, the Japs were frantic and assumed the attack had come from the locals. The Kempei-Tai, (Japanese Military Police) rounded up large numbers of Chinese for ‘interrogation’ at their HQ at the old YMCA. They thoroughly searched our camps and found nothing. Gwen said they took 45 people away but only 15 were returned to the camps.

The treatment of the POWS was shocking as the Japanese already considered them dead. To be captured was a disgrace, death in battle was honourable to the Japanese. In fact the brutality to prisoners was compounded by the belief that these Japanese felt dishonoured at having to guard ‘dead’ prisoners. They believed they should be fighting at the front with the Imperial Japanese Army. So the Japanese kicked hell out of the Korean and Formosan guards who kicked hell out of the prisoners. As the war progressed and Japanese wounded returned from Burma with tales of the terrible conditions there, these guards were not so eager to go to the frontlines.

An unusual feature was the recruitment of some Indian POWs into the new Indian Independence Army run by Chandra Bose. This Army was to help the Japanese Army liberate India but was never really more than a source of labour for the Burma Front and many were just used as additional prison guards. The Ex-British Indian soldiers I saw used as guards, were turbaned Sikhs. To be fair, many Indian soldiers who would not change sides, were used as target practice by Japanese solders. Little paper circles with a black cross were pinned over their hearts as they knelt tied for this exercise. Nice bastards, these Japs!

Having said that, we did have a Jap Officer who loved children. For some reason we called him red socks (stupid name as he wore long boots) and he would throw handfuls of sweets to the children whenever he came to the camp. Apparently this was not the correct conduct for a Japanese Officer and he was transferred to Burma and died there.

The Japanese had a habit of blowing their car horns when they arrived to let us know where to face them and when to bow. This particular day we heard the horns and turned to see an unusual sight, for sitting up on the back seat of an open car, was a soldier in jungle green and wearing a red beret. The excitement of seeing a British Officer, was overwhelming and when he stepped up to accept the swords of the Japanese Officers lined up, everyone cheered. Mum said the only Officer to refuse his sword was Tominaga and when the British Officer kicked him in the backside, he quickly offered it. For us, the war was over. I was seven that September.We were held for some time as the medical teams moved in. Then we went to the Sea View Hotel by the beach where the children were given sea rides in Army DUKWs or ‘Ducks’ and I had my first ice cream. I saw my first moving picture and my first one in colour. There was a reception at the Municipal Building for the Internees and Lord Louis Mountbatten and his wife spoke to Mum and Dad and they were thrilled to have met this great man. He even had me on his knee at one stage, according to Mum.

Some instant judgements were made and public executions were held outside Changi. I saw one where Japanese and Korean guards, obviously identified by POWs, were hanged on a 10-man scaffold with the Public treating it as a Fair. The Chinese especially, had suffered and were determined to celebrate. During the war, the Japs had many Chinese severed heads on poles along the streets to warn the Chinese population against anti-Japanese actions.

Now there were makan (food) carts, peanut vendors and drink sellers catering to a large crowd. The prisoners were to be hung according to their weight and the ropes were prepared accordingly, but the officer marched them out in the wrong order and the fat Jap got the long rope meant for the lighter man. When the trapdoors opened, the officer realised his mistake. He examined the fat Jap first and pronounced him dead and by the time he reached the last one, the thin Jap with the short rope, he had strangled to death. One wounded Jap, perhaps a failed hara-kiri attempt, was brought out in a wheelchair and shot.

When executions were by shooting, all the children would run to collect the ejected .303” shell casings as these could be pushed onto short pencils and would extend their useful life. The last inch could still be used and as pencils were in short supply, you could always sell a casing for 5 or 10 cents but you could get double that if you could say it had killed a Jap. Ah, the commercial possibilities for a child.

We would hear the distinct sound of Kendo when the Japanese Officers practiced their swordplay. The clash of bamboo against bamboo, helmet and breastplates and the yells of the men would penetrate down to the huts from the guardhouse and the Commandant’s house on the hill.

Towards the end of the war, the skies were filled with Allied planes from Burma and sometimes they would drop Red Cross parcels. The Guards would fire their single AA gun and we saw the black puffs of smoke well below the planes. If any parachutes landed within the camp, we tried to hide the boxes before the Japs ran down from the guardhouse and collected them. Once we did manage to save one parcel and our whole hut of 30 shared the contents. It had Canadian Red Cross stamped on the side and we excitedly opened it. I remember the paper straw packing, the tins of meat, butter, cigarettes, and even chewing gum. Mum and I received 2 tins of Condensed Milk and for my sixth birthday, we ate a tin each. This had turned hard in the tropical heat and was like caramel and we were both very ill later.

The Japanese instructed the women to sew caps and make kidney belts for their troops and they would receive extra food for their children. Mum refused and was noted as a troublemaker. When a couple of women had affairs with Japanese Officers, Mum went up to them and said ‘this war will not last forever and you will pay’. They must have mentioned this to the officers because later when there was an inspection for hidden radios, Mum was take to the guard house, raped, then beaten with a hoe handle and baseball bat and kept there for a week. She admits she was very lucky to return.

After the war these women quickly left but Mum was a chief witness at the War Trials held in Singapore. She was instrumental in getting Commandant Tominaga, executed and was commended for her clear testimony by the Judge. Mum also said that when the commando ship the ‘Krait’ slipped into Singapore Harbour and the men of Z Force sank all that shipping, the Japs were frantic and assumed the attack had come from the locals. The Kempei-Tai, (Japanese Military Police) rounded up large numbers of Chinese for ‘interrogation’ at their HQ at the old YMCA. They thoroughly searched our camps and found nothing. Gwen said they took 45 people away but only 15 were returned to the camps.

The treatment of the POWS was shocking as the Japanese already considered them dead. To be captured was a disgrace, death in battle was honourable to the Japanese. In fact the brutality to prisoners was compounded by the belief that these Japanese felt dishonoured at having to guard ‘dead’ prisoners. They believed they should be fighting at the front with the Imperial Japanese Army. So the Japanese kicked hell out of the Korean and Formosan guards who kicked hell out of the prisoners. As the war progressed and Japanese wounded returned from Burma with tales of the terrible conditions there, these guards were not so eager to go to the frontlines.

An unusual feature was the recruitment of some Indian POWs into the new Indian Independence Army run by Chandra Bose. This Army was to help the Japanese Army liberate India but was never really more than a source of labour for the Burma Front and many were just used as additional prison guards. The Ex-British Indian soldiers I saw used as guards, were turbaned Sikhs. To be fair, many Indian soldiers who would not change sides, were used as target practice by Japanese solders. Little paper circles with a black cross were pinned over their hearts as they knelt tied for this exercise. Nice bastards, these Japs!

Having said that, we did have a Jap Officer who loved children. For some reason we called him red socks (stupid name as he wore long boots) and he would throw handfuls of sweets to the children whenever he came to the camp. Apparently this was not the correct conduct for a Japanese Officer and he was transferred to Burma and died there.

The Japanese had a habit of blowing their car horns when they arrived to let us know where to face them and when to bow. This particular day we heard the horns and turned to see an unusual sight, for sitting up on the back seat of an open car, was a soldier in jungle green and wearing a red beret. The excitement of seeing a British Officer, was overwhelming and when he stepped up to accept the swords of the Japanese Officers lined up, everyone cheered. Mum said the only Officer to refuse his sword was Tominaga and when the British Officer kicked him in the backside, he quickly offered it. For us, the war was over. I was seven that September.We were held for some time as the medical teams moved in. Then we went to the Sea View Hotel by the beach where the children were given sea rides in Army DUKWs or ‘Ducks’ and I had my first ice cream. I saw my first moving picture and my first one in colour. There was a reception at the Municipal Building for the Internees and Lord Louis Mountbatten and his wife spoke to Mum and Dad and they were thrilled to have met this great man. He even had me on his knee at one stage, according to Mum.

Some instant judgements were made and public executions were held outside Changi. I saw one where Japanese and Korean guards, obviously identified by POWs, were hanged on a 10-man scaffold with the Public treating it as a Fair. The Chinese especially, had suffered and were determined to celebrate. During the war, the Japs had many Chinese severed heads on poles along the streets to warn the Chinese population against anti-Japanese actions.

Now there were makan (food) carts, peanut vendors and drink sellers catering to a large crowd. The prisoners were to be hung according to their weight and the ropes were prepared accordingly, but the officer marched them out in the wrong order and the fat Jap got the long rope meant for the lighter man. When the trapdoors opened, the officer realised his mistake. He examined the fat Jap first and pronounced him dead and by the time he reached the last one, the thin Jap with the short rope, he had strangled to death. One wounded Jap, perhaps a failed hara-kiri attempt, was brought out in a wheelchair and shot.

When executions were by shooting, all the children would run to collect the ejected .303” shell casings as these could be pushed onto short pencils and would extend their useful life. The last inch could still be used and as pencils were in short supply, you could always sell a casing for 5 or 10 cents but you could get double that if you could say it had killed a Jap. Ah, the commercial possibilities for a child.

Chapter 2 – Penang –1946-1951

Bertie decided his family needed to get away, so we moved to Penang Island in 1946, where he started his stable again. We had nothing left and it was hard for him, he was 67 and his health was bad. His 4 houses were gone and the Japanese had transported all his horses to Japan so he had to start again. His wonderful large collection of trophies, both from racing and sharp shooting, were gone as were all his silver-plated handguns and his specialist range rifles. Mum had to go back to Singapore for the War Trials and racing had changed with the arrival of new trainers and jockeys. Dad said it was no longer a Gentleman’s Sport and horses were being pulled and drugged. He refused to change his methods and gradually lost his horses to other trainers.

Bertie decided his family needed to get away, so we moved to Penang Island in 1946, where he started his stable again. We had nothing left and it was hard for him, he was 67 and his health was bad. His 4 houses were gone and the Japanese had transported all his horses to Japan so he had to start again. His wonderful large collection of trophies, both from racing and sharp shooting, were gone as were all his silver-plated handguns and his specialist range rifles. Mum had to go back to Singapore for the War Trials and racing had changed with the arrival of new trainers and jockeys. Dad said it was no longer a Gentleman’s Sport and horses were being pulled and drugged. He refused to change his methods and gradually lost his horses to other trainers.

|

My brother Laurie was born in 1948 and the Malayan Emergency started. The Japanese took the whole of Malaya fighting an Army, in 6 weeks. The British took 6 months to re-occupy a surrendered country. Admittedly, the priority was to care for the thousands of POWs, but with the Japanese in their barracks waiting to hand over to the British, the Communists came out of the jungles and settled old scores. The Communists, who had been a large part of the Anti-Japanese Army fighting the Japs, had been refused permission to take part in the Victory Parade. The Cold War had started and so the Communists moved back into the jungle, dug up their British-supplied weapons and began the guerilla war. The Terrorists were bombing theatres, shooting Police and Special Constables and attacking plantations. Soon, troops from Britain, Australia and New Zealand were involved in a full-scale jungle war.

Bertie thought that the situation was getting worse and wanted his sons back in Australia so we left in June 1951, after saying goodbye to Pat and his wife. We lost track of them and did not find them again for 35 years. Mum did not want to leave and to her last years in Australia, refused to believe that Malaya and Singapore had changed and that they were still the same as under the British. She did go back in 1980 for a 3 month holiday but returned in 3 weeks and never spoke about it. We arrived in Brisbane in the winter. Dad was a sick man and nearly 72 years old and Mum had to learn to cook, keep house, do the washing and eventually go to work. |

She always had Amahs to do the work and hated her changed life. I left school at 17 to help and eventually went to Darwin in October 1959 as a Cartographer with the Lands and Survey Branch. Dad, Mum and Laurie followed 4 months later. Dad died in 1961, 4 days short of his 82 birthday. He always said, ‘better a Has-Been than a Never-Waser!’. He had had a marvelous life in spite of his last few years. Mum commenced her wanderings to Fiji, PNG and North Queensland and died aged 67, in Brisbane in 1981. Her ashes were interred in Bertie’s grave (#203) in Darwin as requested.

My half-brother Pat survived the war. He was captured in Java and sent to Kuching in Borneo, working on airstrips and roads, and said he was one of the lucky 600 of his 10,000 to survive. He said he was too sick to be selected for the proposed re-enforcement of the Australian POWs at Sandakan. Just as well, as only 6 Australians out of 2400 or so, survived that march. After the war, the International Red Cross informed Pat of the whereabouts of his family. He managed to scrounge a lift to Cairo, Egypt, by plane and made his way down the East Coast of Africa to find his family at Durban, South Africa. He returned to his Tin Mining Company in Ipoh, Malaya and later his home in Perth. He died in Brisbane in 1995.

Chapter 3 – the Lighter Side of Penang

I loved my beautiful Penang Island. Dad was pre-occupied with his stable and Mum would be at the milliner’s and tailor’s every Wednesday preparing a new outfit for the next Race Day. The competition between the women in the Racing fraternity, was as intense as before the war. It was a good life, not as good as before the war, but still very good. After all, the locals had seen an Asian Army beat the crap out of a European Army and things could never be the same.

The British had justified the loss of Malaya and Singapore, saying, that by saving their UK Islands first, there was a chance of recapturing the Colonies later. The Asians said a tigress would never leave her cubs and would fight to the death to protect them.

I know my parents loved me, but I was, for the most part, ignored. I did not fit in with their social life. This meant I grew up with tremendous freedom and I used it. Our first home was in Peel Avenue opposite the Police Barrack complex. It had wide spacious grounds and even an old concrete blockhouse covered in bougainvillea, which I used as a fort. The wide, covered, circular verandah was ideal for my many Dinky Toy cars but I always had the feeling that someone was watching me, that I was not alone. Nothing scary, I just kept turning to see who was there. The locals said the Japs who occupied the house, had a number of women there and treated them badly and some had died.

The large open storm drain between us and Peel Avenue, had a good coating of green algae and we kids used it for bare foot skiing but had to keep an eye out for broken bottles. Another sport was to climb the large trees and, with a stick, flick the 2 to 3 foot green tree snakes off the branches and watch them fall.

My half-brother Pat survived the war. He was captured in Java and sent to Kuching in Borneo, working on airstrips and roads, and said he was one of the lucky 600 of his 10,000 to survive. He said he was too sick to be selected for the proposed re-enforcement of the Australian POWs at Sandakan. Just as well, as only 6 Australians out of 2400 or so, survived that march. After the war, the International Red Cross informed Pat of the whereabouts of his family. He managed to scrounge a lift to Cairo, Egypt, by plane and made his way down the East Coast of Africa to find his family at Durban, South Africa. He returned to his Tin Mining Company in Ipoh, Malaya and later his home in Perth. He died in Brisbane in 1995.

Chapter 3 – the Lighter Side of Penang

I loved my beautiful Penang Island. Dad was pre-occupied with his stable and Mum would be at the milliner’s and tailor’s every Wednesday preparing a new outfit for the next Race Day. The competition between the women in the Racing fraternity, was as intense as before the war. It was a good life, not as good as before the war, but still very good. After all, the locals had seen an Asian Army beat the crap out of a European Army and things could never be the same.

The British had justified the loss of Malaya and Singapore, saying, that by saving their UK Islands first, there was a chance of recapturing the Colonies later. The Asians said a tigress would never leave her cubs and would fight to the death to protect them.

I know my parents loved me, but I was, for the most part, ignored. I did not fit in with their social life. This meant I grew up with tremendous freedom and I used it. Our first home was in Peel Avenue opposite the Police Barrack complex. It had wide spacious grounds and even an old concrete blockhouse covered in bougainvillea, which I used as a fort. The wide, covered, circular verandah was ideal for my many Dinky Toy cars but I always had the feeling that someone was watching me, that I was not alone. Nothing scary, I just kept turning to see who was there. The locals said the Japs who occupied the house, had a number of women there and treated them badly and some had died.

The large open storm drain between us and Peel Avenue, had a good coating of green algae and we kids used it for bare foot skiing but had to keep an eye out for broken bottles. Another sport was to climb the large trees and, with a stick, flick the 2 to 3 foot green tree snakes off the branches and watch them fall.

|

We moved to 673 Waterfall Rd, near the beautiful Botanical Gardens, which was in a natural horseshoe valley. It was heaven. We had Waterfall Creek behind us and after the rains, we would see a huge column of black-red termites on the move on the trail to the Gardens. We called them Soldier Ants of course, but the columns would be over 2 feet wide and stretch for nearly half a mile. We often broke the column with our feet or a stick, only to see them reform and continue. The path wound for 5 miles to the Botanical Gardens and the way was interrupted by collapsing Jap tunnels, which we would explored very timidly, never going beyond the sunlit sections. There were stories of rice and other stores still hidden in these tunnels.

|

Ah Kum, Gwen, Ah Haw and Laurie in our trishaw

Ah Kum, Gwen, Ah Haw and Laurie in our trishaw

The wild monkeys used our house as part of their route to the trees on the creek. They would come down from the hills opposite, swing through the trees and sometimes they missed a branch over the road and hit the powerlines and zap - barbequed monkey! They would flick the tiles off our roof, enjoying the sound of the tiles smashed on the concrete. Dad had to obtain a handgun from the Police and shoot some of the aggressive males who threatened us when we tried to stop this damage. Though we had bars on the windows for larger animals, squirrels came in at night and scrambled up and down our mosquito nets.

The only open ground we had was the old Chinese Cemetery behind the creek on the next hill. This is where we flew our kites. The locals had a passion for kite fighting. Your kite would be immediately challenged any flying kite. The first 200 feet of string was coated with fine powered bottle glass mixed with glue, an egg and blue colouring. The egg was for flexibility, and the blue was to hide the string against the sky. This allowed you to manoevour your kite and cut the enemy’s line. Whoever reached the ‘downed’ kite was the new owner. This meant that scores of young kids chased these falling kites all over the place and collected them from trees and powerlines with long bamboo poles. This was very dangerous as they ran across roads without looking out for traffic. They’d sell any back to the shops where people like me would go to replace my lost kite. Often, to gain height for the kites, we would run along the tops of the graves and occasionally our feet would break through the crust, leaving a series of holes.

There was a Malay down the road, who made kites for a living. He lived in an attap roofed wooden house and was able to support 4 wives and 6 children. His first wife was head of the home, the second ran the domestic side, did the cooking etc. The third wife cared for the children and his new fourth wife was only sixteen years old. It was quite common in those days to find Muslims with 4 wives and large families. I often wondered how he supported his family when the kite season was over.

A Chinese funeral was a sight to behold. It depended on how rich the dead man was, but the paid professional wailers, all dressed in white, the colour of mourning, would cry and rant and beat their heads, really put on a good show. The red paper models of cars, boats, houses and paper money were burnt to accompany the deceased on his journey to the New World. Often, the Chinese would leave food and drink on the graves of their loved ones as we would leave flowers. They seemed happy to find the offering accepted the next day and there were many beggars with full bellies.

We used to have fighting fish. These were dull gray fish about 2-3 inches long, from the padi-fields, but we‘d put each in a jar and at the back of a closet in the dark. Soon, they turned into a brilliant black-blue colour and were really mean and angry. We took our fish to school and after betting 5 or 10 cents, we’d put the 2 fighters together and watch the battle. When one was the obvious winner, we‘d separate them and collect our money if any. The current Siamese Fighting Fish are bred for their colours and long fins and would not last 10 seconds with our fighters.

Spiders were another form of betting. We’d each have a small spider in a tobacco tin and then place 2 spiders on the lid. They’d lift their main front legs and push each other until one broke and ran. This was something any schoolboy could afford as these spiders were everywhere. Our schools were fully used and would have a morning and an afternoon shift. The younger classes would get the early shift and often there was congestion as the 2 groups passed each other, one moving out and the other going in.

The British soldiers made good use of the Botanical Gardens. In the evenings, the trishaws with the soldiers and their Chinese girls would head for the Gardens. For some reason, perhaps as a sign of their success, they all left their used condoms hanging from various bushes. The Indian gardeners had to harvest these unusual flowers every morning before the gates were opened to the public.

As I was reaching that age and things were stirring, my Indian mates and I made great use of this learning facility so close by. On moonlight nights we went scouting for lovers and we each had our own park bench to observe. My favorite was a bench under a huge tree I climbed and could look down in safety. This night a Chinese man and his girl friend arrived and he leaned his bicycle against the tree. They were soon very busy, then this tiger wandered down to the creek, 30 feet away. It was clearly visible in the bright moonlight. The man disengaged himself, slowly backed off, grabbed the bicycle, and took off down the road, screaming ‘rimau, rimau’ (tiger, tiger). The tiger, after his drink, walked by, stopped 20 feet away and looked at the woman with complete disinterest, then continued into the jungle. The woman then quickly left and after some time, I climbed down, joined my mates who had seen it all and we got out of there.

A safer option was the Moon Gate half way to the Gardens. This was then a crumbling Chinese style wall with a circular opening or door. It was the start of a four and a half mile steep climb to Government Hill overlooking Georgetown, the Capital. It was great, a four and a half hour slow walk up and a half hour run down. We kids were very fit but the interesting part was on several of the zigzag corners, Indian Holy men were doing their penance. You would see a man who was fasting for months, one who took a vow to stand all his life and had this contraption built propping his body up. Another would never cut his fingernails and they would curl into spring-like coils and his hands were completely useless. Others took a vow of silence, fascinating stuff I will always remember.

Every year the Indians held a Festival called Thaipusum. It was held at a temple in my Waterfall Road and I never missed it. This was the time you could wash your sins away by enduring pain, that is, by sticking yourself with barbless hooks and skewers. The men would carry a kavardi or structure with a God on their shoulders and supported by a V of skewers hooked into their chest and back. They walked on wooden shoes with the nails upright and often pulled a small trolley hooked to their back skin also carrying a God. They were in a trance with a white liquid where there should have been blood. All, including women, had a skewer through the cheeks and also the tongue. The procession would wind up 600 steps to a temple on the hill where everything was removed. This is still held today.

Before I was allowed to cycle to school, I went by pedal trishaw and on the way home we would stop at the small town of Pulau Tikus, or Island of Rats, at the end of Burma Road. I’d cross the road to the Newsagent and check if my Dandy and Beeno comics had arrived from the UK. Sami, my trishaw peddler, went to the opium den opposite, next to the bicycle repair shop, and settled down with a pipeful. When I was ready, we continued home.

There were many older Chinese women in Pulau Tikus, hobbling painfully, their feet bounded up in the traditional way. The Chinese men stressed that to be regarded as beautiful, women had to have small or tiny feet. So from childhood these women’s mothers bounded their feet up tightly in bandages, restricting growth at the expense of crushed and broken bones and a lifetime of pain, walking on deformed feet. This may have been just a ploy to ensure that their wives and concubines were not able to run away if unhappy.

There was a large Christian cemetery along Western Road. One of our challenges, late at night, was to run through one gate, along the winding pathway to the other gate, at one minute intervals. Many a record was broken by frightened 10 and 12 year olds!

Gwen loved music and we had a standing order for 78 rpm records. We collected tenors Richard Tauber, Richard Crooks, Joseph Schmidt and John McCormack. I got my love for Irish, Welsh and Scottish ballads from Mum and Dad would narrate a few Bush songs from his childhood. I collected cowboy singers like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. You know, they made the kind of films where they would say, ‘lets save the homesteaders from the Indians but first we‘ll sing a little song’ The Chinese shop-owner knew he had a good customer and canvassed all the ships unloading in the harbour for new records.

The pictures in Penang would have special serial marathons. Usually you would see one episode of Buck Rogers and then come back next week to follow the next part. Well, they would string the lot together so you would see 48 episodes of Zorro in 6 hours and the same with Buck Rogers, Captain Marvel and any Buster Crabbe epic like ‘the Sea Spray’.

One day I was at the pictures and talking to 2 Aussie soldiers who asked my name. My nickname was Winkie and they said “no, what is it really” I told them it was William. They said in Australia, I’d be called Bill. What a cool, tough name I thought and I got home to tell Dad and Mum that I was to be called Bill. Dad did so but I was still Winkie to Mum for some time.

Mum dreaded Mondays, that was laundry day. The Indian Dobbie or washerman would arrive and Mum would have to list all the sheets, shirts etc going out and on Thursday marked them back. The Dobbie would wrap the clothes and sheets in one of the large bedsheets, tie the corners together and trudge off, carrying it on his back. He would wash the clothes the usual way by pounding it on flat rocks in the river and then return with all the clothes ironed and starched and the sheets spotless. Needless to say, clothes did not last long but they were always clean.

We had two Amahs or servants. Ah Kum was slightly built, did the cooking and looked after the house. Oh, she also buttered my bread until I was 12 so I guess I was pretty spoilt. Ah Haw was heavier, looked after my brother Laurie and often took him for long walks in his pram. There was one time when a very heavy downpour caught them a couple of miles away and Dad who had the car, should have picked them up. However he was at his club and she had to push Laurie home in the rain. Both were completely soaked and when Dad got home, she abused hell out of him. Dad was so shocked he said nothing but Mum had to tell her to shut up. Ah Haw was right of course and Dad knew it. She kept her job as she proved she was concerned about young Laurie.

These Chinese women had their own families somewhere and saw them on their off days. They both contributed to a Konksi House. This was an early form of old age security run by their ‘union’ where they were assured of accommodation and food if unemployed, ill or retired.

Dad would take me to the track to watch the horses work on some weekends. He had an Arial Square Four motorcycle with an old BSA Army sidecar and we’d ride off down Western Road to the Turf Club. I’d sit above the Jockeys’ Building as he trained his horses. We’d be home by 10 am. On race-days, I could see the jockeys changing and weighing in before and after a race and I had the best view of all aspects of the track. The building is still there but had been extended upwards and the small vent windows on the roof I’d peer down through, are now full size and part of the new floor.

There was a wonderful Indian Cake-seller next to us. He lived in an attap hut with an earthen floor painted with a mixture of cowdung and water, a cheap form of cement there. This meant the chickens would feed all through the 3 room hut, pecking at the freshly painted floor. He had a tired wife, 4 boys and 3 girls. Every morning at 5am he’d shouldered his 2 four trayed baskets of cakes on a pole and walk to the village and houses to sell his wares and return late in the evening. I would sometimes share breakfast with them and Mum was furious. ‘Why do you take from people who have so little?’ My answer was their meals of curry gravy and chapatti was tastier than ours.

My Mum often sent our own European Doctor if anyone was very ill and they never forgot that. Many years later, when Trish and I visited, they invited us in. The house now had a tin roof and wooden sides. It had a real concrete floor and looked quite prosperous. The girls were married off at the age of 14, often to men 15-20 years older. The boys had always been expected to financially care for their old parents. This is why they had so many children, so the survivors could look after them. The infant death rate was high and this was their security. The first son was now a railway porter, the second and third were teachers in my old School and the fourth was a soldier in the Malayan Army. The old man had worked hard for his children and they had obviously done well and honoured their commitments.

The Chinese family next to them had another attap house with 4 rooms. The father was a powder monkey, an explosives man in a quarry. He had a wife, 2 boys and 2 girls and took in another Chinese family to help financially. I would play hide and seek right around the house with the kids and it was easy to look under the walls as the attap sides did not touch the floor. One day, the Police raided and arrested the second family and they found a printing press dug into the floor of their small room. He had been printing money and the Police did not believe the owner did not know anything about it and arrested him also. I had never seen nor suspected anything and I was there a lot. Anyway, Mum went into Court to bat for him and got him released. I don’t know how this other guy dug the hole, removed the dirt, moved the machinery in and worked the presses without any of the others knowing, I mean you could see under the walls! When we met the owner’s son, Say Wah, years later, he said his father was dead, blown up in the quarry.

We had the Amahs’ quarters behind our house and it was on filled ground as the land sloped down towards the creek. Inside the cracked retaining wall lived a large python, about 20 feet. It would come out every 2 months and steal a chicken or piglet from the neighbours and returned to the wall. We never had any trouble with it but we did with cobras. The area between the house and the Amahs’ quarters was concreted and this attracted the black cobras enjoying the sun. The Amahs would yell and scream and batter them with long bamboo poles and flick the remains into the bush. Some I would kill with my home-made bamboo bow and arrows. We killed an average of one a fortnight, each was about 5 feet long.

Our house was up on brick piers and the car was garaged under. The bathroom was below and set half-buried into the ground. Tap water flowed onto a huge Ali Baba type earthen jar and you bathed by scooping the water out with a ladle. The area was always damp and we had plenty of 8 -10 inch centipedes, which entered through the many drain holes. Often when on the pan toilet, you had to keep your legs up off the floor as a precaution. A bit scary in the semi dark!

There were cashew trees near the Chinese cemetery behind us and one day, as we collected some nuts, a deep growl came from the overhanging branches. We took off downhill but halfway, Mum stopped. She decided that someone was playing a trick and wanted our dropped cashews and went back. A second growl and Mum flashed passed us and we followed her. It rained heavily that night and the next day we went back with a Government hunter. The rain had damaged the lair of a Black Panther and the hunter found tracks of the Panther and her cub leading up to the Gardens. He said we were very lucky, as we got the second warning only because she was protecting her cub.

To the south of Georgetown the Capital, there was a Chinese Temple full of snakes of all sizes. These would hang from light fittings and rafters, coiled around rungs of the many ladders against the walls and with dozens of tiny baby snakes in shrubs in plant pots lining both sides of the corridors. They were mainly the harmless green tree snakes and so doped up on the heavy incense from thousands of smoking joss sticks, which filled the whole Temple. Outside were large concrete cages with some huge pythons, which were fed chickens or rats daily. There was no entry charge to the Snake Temple, but you were asked for a donation before you were allowed to leave. Most women visitors were only too pleased to pay this to get out. This is still operating today I think.

My brother Laurie was born in 1948 and the Emergency had steadily got worse with bombings and shootings. Police and Special Constables were out in force and there were troops in the jungles chasing the ‘Bandits’ as the Communists were called. Dad’s business was failing as was his health and he was afraid of another war. Gwen was very upset as she did not want to leave her beautiful Malaya, but we packed up, flew to Singapore and sailed for Brisbane on the MV Merkur in June 1951.

The only open ground we had was the old Chinese Cemetery behind the creek on the next hill. This is where we flew our kites. The locals had a passion for kite fighting. Your kite would be immediately challenged any flying kite. The first 200 feet of string was coated with fine powered bottle glass mixed with glue, an egg and blue colouring. The egg was for flexibility, and the blue was to hide the string against the sky. This allowed you to manoevour your kite and cut the enemy’s line. Whoever reached the ‘downed’ kite was the new owner. This meant that scores of young kids chased these falling kites all over the place and collected them from trees and powerlines with long bamboo poles. This was very dangerous as they ran across roads without looking out for traffic. They’d sell any back to the shops where people like me would go to replace my lost kite. Often, to gain height for the kites, we would run along the tops of the graves and occasionally our feet would break through the crust, leaving a series of holes.

There was a Malay down the road, who made kites for a living. He lived in an attap roofed wooden house and was able to support 4 wives and 6 children. His first wife was head of the home, the second ran the domestic side, did the cooking etc. The third wife cared for the children and his new fourth wife was only sixteen years old. It was quite common in those days to find Muslims with 4 wives and large families. I often wondered how he supported his family when the kite season was over.

A Chinese funeral was a sight to behold. It depended on how rich the dead man was, but the paid professional wailers, all dressed in white, the colour of mourning, would cry and rant and beat their heads, really put on a good show. The red paper models of cars, boats, houses and paper money were burnt to accompany the deceased on his journey to the New World. Often, the Chinese would leave food and drink on the graves of their loved ones as we would leave flowers. They seemed happy to find the offering accepted the next day and there were many beggars with full bellies.

We used to have fighting fish. These were dull gray fish about 2-3 inches long, from the padi-fields, but we‘d put each in a jar and at the back of a closet in the dark. Soon, they turned into a brilliant black-blue colour and were really mean and angry. We took our fish to school and after betting 5 or 10 cents, we’d put the 2 fighters together and watch the battle. When one was the obvious winner, we‘d separate them and collect our money if any. The current Siamese Fighting Fish are bred for their colours and long fins and would not last 10 seconds with our fighters.

Spiders were another form of betting. We’d each have a small spider in a tobacco tin and then place 2 spiders on the lid. They’d lift their main front legs and push each other until one broke and ran. This was something any schoolboy could afford as these spiders were everywhere. Our schools were fully used and would have a morning and an afternoon shift. The younger classes would get the early shift and often there was congestion as the 2 groups passed each other, one moving out and the other going in.

The British soldiers made good use of the Botanical Gardens. In the evenings, the trishaws with the soldiers and their Chinese girls would head for the Gardens. For some reason, perhaps as a sign of their success, they all left their used condoms hanging from various bushes. The Indian gardeners had to harvest these unusual flowers every morning before the gates were opened to the public.

As I was reaching that age and things were stirring, my Indian mates and I made great use of this learning facility so close by. On moonlight nights we went scouting for lovers and we each had our own park bench to observe. My favorite was a bench under a huge tree I climbed and could look down in safety. This night a Chinese man and his girl friend arrived and he leaned his bicycle against the tree. They were soon very busy, then this tiger wandered down to the creek, 30 feet away. It was clearly visible in the bright moonlight. The man disengaged himself, slowly backed off, grabbed the bicycle, and took off down the road, screaming ‘rimau, rimau’ (tiger, tiger). The tiger, after his drink, walked by, stopped 20 feet away and looked at the woman with complete disinterest, then continued into the jungle. The woman then quickly left and after some time, I climbed down, joined my mates who had seen it all and we got out of there.

A safer option was the Moon Gate half way to the Gardens. This was then a crumbling Chinese style wall with a circular opening or door. It was the start of a four and a half mile steep climb to Government Hill overlooking Georgetown, the Capital. It was great, a four and a half hour slow walk up and a half hour run down. We kids were very fit but the interesting part was on several of the zigzag corners, Indian Holy men were doing their penance. You would see a man who was fasting for months, one who took a vow to stand all his life and had this contraption built propping his body up. Another would never cut his fingernails and they would curl into spring-like coils and his hands were completely useless. Others took a vow of silence, fascinating stuff I will always remember.

Every year the Indians held a Festival called Thaipusum. It was held at a temple in my Waterfall Road and I never missed it. This was the time you could wash your sins away by enduring pain, that is, by sticking yourself with barbless hooks and skewers. The men would carry a kavardi or structure with a God on their shoulders and supported by a V of skewers hooked into their chest and back. They walked on wooden shoes with the nails upright and often pulled a small trolley hooked to their back skin also carrying a God. They were in a trance with a white liquid where there should have been blood. All, including women, had a skewer through the cheeks and also the tongue. The procession would wind up 600 steps to a temple on the hill where everything was removed. This is still held today.

Before I was allowed to cycle to school, I went by pedal trishaw and on the way home we would stop at the small town of Pulau Tikus, or Island of Rats, at the end of Burma Road. I’d cross the road to the Newsagent and check if my Dandy and Beeno comics had arrived from the UK. Sami, my trishaw peddler, went to the opium den opposite, next to the bicycle repair shop, and settled down with a pipeful. When I was ready, we continued home.

There were many older Chinese women in Pulau Tikus, hobbling painfully, their feet bounded up in the traditional way. The Chinese men stressed that to be regarded as beautiful, women had to have small or tiny feet. So from childhood these women’s mothers bounded their feet up tightly in bandages, restricting growth at the expense of crushed and broken bones and a lifetime of pain, walking on deformed feet. This may have been just a ploy to ensure that their wives and concubines were not able to run away if unhappy.

There was a large Christian cemetery along Western Road. One of our challenges, late at night, was to run through one gate, along the winding pathway to the other gate, at one minute intervals. Many a record was broken by frightened 10 and 12 year olds!

Gwen loved music and we had a standing order for 78 rpm records. We collected tenors Richard Tauber, Richard Crooks, Joseph Schmidt and John McCormack. I got my love for Irish, Welsh and Scottish ballads from Mum and Dad would narrate a few Bush songs from his childhood. I collected cowboy singers like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. You know, they made the kind of films where they would say, ‘lets save the homesteaders from the Indians but first we‘ll sing a little song’ The Chinese shop-owner knew he had a good customer and canvassed all the ships unloading in the harbour for new records.

The pictures in Penang would have special serial marathons. Usually you would see one episode of Buck Rogers and then come back next week to follow the next part. Well, they would string the lot together so you would see 48 episodes of Zorro in 6 hours and the same with Buck Rogers, Captain Marvel and any Buster Crabbe epic like ‘the Sea Spray’.

One day I was at the pictures and talking to 2 Aussie soldiers who asked my name. My nickname was Winkie and they said “no, what is it really” I told them it was William. They said in Australia, I’d be called Bill. What a cool, tough name I thought and I got home to tell Dad and Mum that I was to be called Bill. Dad did so but I was still Winkie to Mum for some time.

Mum dreaded Mondays, that was laundry day. The Indian Dobbie or washerman would arrive and Mum would have to list all the sheets, shirts etc going out and on Thursday marked them back. The Dobbie would wrap the clothes and sheets in one of the large bedsheets, tie the corners together and trudge off, carrying it on his back. He would wash the clothes the usual way by pounding it on flat rocks in the river and then return with all the clothes ironed and starched and the sheets spotless. Needless to say, clothes did not last long but they were always clean.

We had two Amahs or servants. Ah Kum was slightly built, did the cooking and looked after the house. Oh, she also buttered my bread until I was 12 so I guess I was pretty spoilt. Ah Haw was heavier, looked after my brother Laurie and often took him for long walks in his pram. There was one time when a very heavy downpour caught them a couple of miles away and Dad who had the car, should have picked them up. However he was at his club and she had to push Laurie home in the rain. Both were completely soaked and when Dad got home, she abused hell out of him. Dad was so shocked he said nothing but Mum had to tell her to shut up. Ah Haw was right of course and Dad knew it. She kept her job as she proved she was concerned about young Laurie.

These Chinese women had their own families somewhere and saw them on their off days. They both contributed to a Konksi House. This was an early form of old age security run by their ‘union’ where they were assured of accommodation and food if unemployed, ill or retired.

Dad would take me to the track to watch the horses work on some weekends. He had an Arial Square Four motorcycle with an old BSA Army sidecar and we’d ride off down Western Road to the Turf Club. I’d sit above the Jockeys’ Building as he trained his horses. We’d be home by 10 am. On race-days, I could see the jockeys changing and weighing in before and after a race and I had the best view of all aspects of the track. The building is still there but had been extended upwards and the small vent windows on the roof I’d peer down through, are now full size and part of the new floor.

There was a wonderful Indian Cake-seller next to us. He lived in an attap hut with an earthen floor painted with a mixture of cowdung and water, a cheap form of cement there. This meant the chickens would feed all through the 3 room hut, pecking at the freshly painted floor. He had a tired wife, 4 boys and 3 girls. Every morning at 5am he’d shouldered his 2 four trayed baskets of cakes on a pole and walk to the village and houses to sell his wares and return late in the evening. I would sometimes share breakfast with them and Mum was furious. ‘Why do you take from people who have so little?’ My answer was their meals of curry gravy and chapatti was tastier than ours.

My Mum often sent our own European Doctor if anyone was very ill and they never forgot that. Many years later, when Trish and I visited, they invited us in. The house now had a tin roof and wooden sides. It had a real concrete floor and looked quite prosperous. The girls were married off at the age of 14, often to men 15-20 years older. The boys had always been expected to financially care for their old parents. This is why they had so many children, so the survivors could look after them. The infant death rate was high and this was their security. The first son was now a railway porter, the second and third were teachers in my old School and the fourth was a soldier in the Malayan Army. The old man had worked hard for his children and they had obviously done well and honoured their commitments.

The Chinese family next to them had another attap house with 4 rooms. The father was a powder monkey, an explosives man in a quarry. He had a wife, 2 boys and 2 girls and took in another Chinese family to help financially. I would play hide and seek right around the house with the kids and it was easy to look under the walls as the attap sides did not touch the floor. One day, the Police raided and arrested the second family and they found a printing press dug into the floor of their small room. He had been printing money and the Police did not believe the owner did not know anything about it and arrested him also. I had never seen nor suspected anything and I was there a lot. Anyway, Mum went into Court to bat for him and got him released. I don’t know how this other guy dug the hole, removed the dirt, moved the machinery in and worked the presses without any of the others knowing, I mean you could see under the walls! When we met the owner’s son, Say Wah, years later, he said his father was dead, blown up in the quarry.

We had the Amahs’ quarters behind our house and it was on filled ground as the land sloped down towards the creek. Inside the cracked retaining wall lived a large python, about 20 feet. It would come out every 2 months and steal a chicken or piglet from the neighbours and returned to the wall. We never had any trouble with it but we did with cobras. The area between the house and the Amahs’ quarters was concreted and this attracted the black cobras enjoying the sun. The Amahs would yell and scream and batter them with long bamboo poles and flick the remains into the bush. Some I would kill with my home-made bamboo bow and arrows. We killed an average of one a fortnight, each was about 5 feet long.

Our house was up on brick piers and the car was garaged under. The bathroom was below and set half-buried into the ground. Tap water flowed onto a huge Ali Baba type earthen jar and you bathed by scooping the water out with a ladle. The area was always damp and we had plenty of 8 -10 inch centipedes, which entered through the many drain holes. Often when on the pan toilet, you had to keep your legs up off the floor as a precaution. A bit scary in the semi dark!