Evacuation on the SS 'Narkunda' by Alison Williams

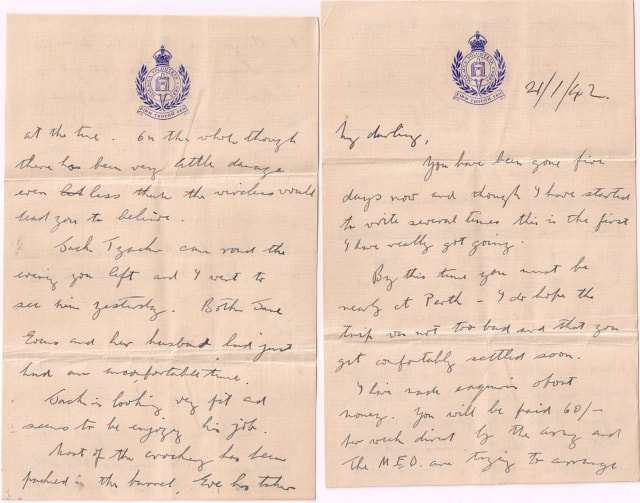

I was born in 1938 and was only three and a half at the time of evacuation so although I have a few very clear memories some of my account comes from what my mother, Vi Webber, told me. There seems to be some confusion on the web about the date of departure of the Narkunda, one entry stating it left with the Aoranji on 16th Jan the other on the 21st. arriving Fremantle on 27th. I had always understood we left on 16th and the passenger list from Fremantle clearly states arrival on 24th. I think you will find the 16th as the date the ship left (see letter...)

In Singapore we were living on Dalvey Estate ( a housing complex not a rubber plantation!) where my father was a Forestry Officer and member of the Volunteers since his time in Johore, joining the 2nd Battalion the Loyals in August 1941. For a time at least he was the Brigade Intelligence Officer (I still have his arm band). My mother worked in Signals. She was one of the first in Singapore to hear the news of the sinking of the “Repulse” and “Prince of Wales”

I remember a little about the weeks before we left for Australia. There was some heavy bombing between Christmas and our departure but I do not remember being afraid - we had a dug out air raid shelter in the garden and a tin hat which I was confident would keep me quite safe. Our house, a two bedroom bungalow, gradually filled up with evacuees from further north. We had friends - I think Eve and Dug Noakes and their son, and also my uncle, Donald Webber, his wife, Pat, and her baby daughter Anna. I remember her sleeping in her cot on the verandah.

We were eventually notified we had passages on an evacuation ship, we being myself, my mother and her sister who had been staying with us. We were allowed two suitcases between us. My mother agonized over what to take but in the end, apart from clothes took only photos and a small silver teapot which had belonged to her mother. Money was another problem as at this stage it was difficult to get any. In the end we left with only my savings from the post office-about £50.

We also had to have all our inoculations including TAB which could make you feel quite ill. To cap it all my mother fell down the cellar steps the night before we left, hitting her head and blacking out for a while. So it was a very sorry small party that boarded the Narkunda the next day. My mother and I were in a cabin originally designed for two but with six berths crowded into it. We only had the one berth between us. My aunt was in another part of the ship.

As the ship left the berth we watched my father, wearing not uniform but white shorts and shirt, until he was out of sight, then went below. In one of the last letters we received before he was taken prisoner he described how he watched us sail out through his very powerful telescope till the ship finally disappeared.

Next morning my mother, usually pretty indomitable, felt so ill she decided to stay in bed. She asked my aunt to take me. She said that she really believed she could not move at that point. The next minute there was an enormous explosion and she found she could race up five flights to the deck in seconds. The gunners had spotted a mine ahead and fired to explode it safely.

I can remember quite clearly our disembarkation at Fremantle. The gang plank was lined with Aussie soldiers who unceremoniously bundled me from one to another while my mother and aunt struggled down with the suitcases. We were put up on camp beds in a school for a while but later, with the help of the wife of an Australian friend, found a house to rent with another family. Later we moved to a bungalow near Perth University, large and comfortable but with an outside lavatory and a water heating system which I thought was called “ the blastedchpeter”- the infamous “chip heater” described by another FEPOW member. Logs were delivered which my mother had to split into chips to feed it. They belched away at the foot of the bath and regularly blew up. There was a wash house too with a copper and mangle. We also had three grape vines, almonds, pomegranate and apricots.

My mother was a Guy’s trained nurse and at once tried to get a job but was told she would have to retrain. She was so incensed at this that she got an office job instead and worked in Perth throughout the war.

The Australians were very kind to us, the weather was great and unlike England we had plenty of good food. But it was a bad time for all the evacuees, waiting for news and getting very little. I will never forget the excitement of the first post card we received- which really only told us my father had been alive six months before. We had four cards in all the three and a half years. So from the beginning my mother had been trying to get back to her family in England.

At last we got a passage but not from Fremantle, from Melbourne. I am glad I can still remember something of the journey across Australia, an experience not to be missed although it took four days in wartime conditions and we had to sit up the whole of the last night. We left from Melbourne on the “Rangitiki” in April 1945. We had three weeks in Wellington where the ship broke down and we were very well entertained by the kind people there. Crossing the Pacific we encountered an enormous storm, the ship literally climbing up the side of waves you could not see over. As with the bombing though, I was not afraid as by this time I could swim. We not only had storms to worry about but mines and torpedoes were still a threat and the daily drills and need to have life jackets with us at all times reminded us of this. The life jackets came with a survival pack of chocolate and milk tablets, whistle and torch. With in a week the former were eaten and the battery of the later used up. Only the whistle remained. The older boys led a wild life on board - I remember them sliding down the ventilation tubes into the hold.

On the 8th May, VE day, we crossed the date line and therefore had a double celebration as we had two Tuesdays, both May the 8th. I still have the menu from dinner signed by all at our table and for wartime a pretty magnificent meal it was.

The Panama Canal was awe inspiring and the lakes beautiful-my mother and I sailed through right in the point of the bow of the ship. At Panama she bought a huge hand of bananas, a few of which survived till England and made us very popular with people who hadn’t seen one in months.

The ship then turned north and we got very cold before it turned across the Atlantic and headed for Liverpool. Entering the Mersey was a terrible experience to those who had been comparatively sheltered from seeing the devastation of war. I counted forty two sunken ships in the approaches and the docks and dockers looked battered and shabby, everything very grey after Australia.

We were home and with our family but the last months until VJ day were hard for my mother. She had had no news of my father for some time and yet everyone around was celebrating as if the war was over. But we were among the lucky ones- my father came safely home. Although his health was damaged and he died young we had nearly twenty years denied many others.

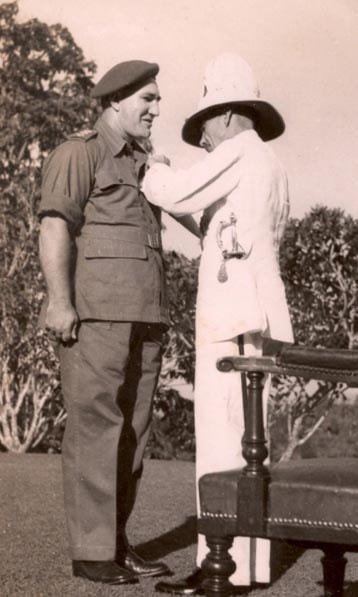

Alison's father Max was awarded the MBE for Services to Prisoners of War. With his brother Donald he had, at great risk, kept a secret radio in captivity and distributed news. The Webber family returned to Malaya post war. During the Malayan Emergency, Max again faced great danger as a Resettlement Officer in Selangor. In 1952 he was awarded the Selangor Conspicuous Gallantry Medal by the Sultan, for saving the life of a wounded police lieutenant during a terrorist ambush on the Jeram-Merbau estates road, Kuala Selangor.

In Singapore we were living on Dalvey Estate ( a housing complex not a rubber plantation!) where my father was a Forestry Officer and member of the Volunteers since his time in Johore, joining the 2nd Battalion the Loyals in August 1941. For a time at least he was the Brigade Intelligence Officer (I still have his arm band). My mother worked in Signals. She was one of the first in Singapore to hear the news of the sinking of the “Repulse” and “Prince of Wales”

I remember a little about the weeks before we left for Australia. There was some heavy bombing between Christmas and our departure but I do not remember being afraid - we had a dug out air raid shelter in the garden and a tin hat which I was confident would keep me quite safe. Our house, a two bedroom bungalow, gradually filled up with evacuees from further north. We had friends - I think Eve and Dug Noakes and their son, and also my uncle, Donald Webber, his wife, Pat, and her baby daughter Anna. I remember her sleeping in her cot on the verandah.

We were eventually notified we had passages on an evacuation ship, we being myself, my mother and her sister who had been staying with us. We were allowed two suitcases between us. My mother agonized over what to take but in the end, apart from clothes took only photos and a small silver teapot which had belonged to her mother. Money was another problem as at this stage it was difficult to get any. In the end we left with only my savings from the post office-about £50.

We also had to have all our inoculations including TAB which could make you feel quite ill. To cap it all my mother fell down the cellar steps the night before we left, hitting her head and blacking out for a while. So it was a very sorry small party that boarded the Narkunda the next day. My mother and I were in a cabin originally designed for two but with six berths crowded into it. We only had the one berth between us. My aunt was in another part of the ship.

As the ship left the berth we watched my father, wearing not uniform but white shorts and shirt, until he was out of sight, then went below. In one of the last letters we received before he was taken prisoner he described how he watched us sail out through his very powerful telescope till the ship finally disappeared.

Next morning my mother, usually pretty indomitable, felt so ill she decided to stay in bed. She asked my aunt to take me. She said that she really believed she could not move at that point. The next minute there was an enormous explosion and she found she could race up five flights to the deck in seconds. The gunners had spotted a mine ahead and fired to explode it safely.

I can remember quite clearly our disembarkation at Fremantle. The gang plank was lined with Aussie soldiers who unceremoniously bundled me from one to another while my mother and aunt struggled down with the suitcases. We were put up on camp beds in a school for a while but later, with the help of the wife of an Australian friend, found a house to rent with another family. Later we moved to a bungalow near Perth University, large and comfortable but with an outside lavatory and a water heating system which I thought was called “ the blastedchpeter”- the infamous “chip heater” described by another FEPOW member. Logs were delivered which my mother had to split into chips to feed it. They belched away at the foot of the bath and regularly blew up. There was a wash house too with a copper and mangle. We also had three grape vines, almonds, pomegranate and apricots.

My mother was a Guy’s trained nurse and at once tried to get a job but was told she would have to retrain. She was so incensed at this that she got an office job instead and worked in Perth throughout the war.

The Australians were very kind to us, the weather was great and unlike England we had plenty of good food. But it was a bad time for all the evacuees, waiting for news and getting very little. I will never forget the excitement of the first post card we received- which really only told us my father had been alive six months before. We had four cards in all the three and a half years. So from the beginning my mother had been trying to get back to her family in England.

At last we got a passage but not from Fremantle, from Melbourne. I am glad I can still remember something of the journey across Australia, an experience not to be missed although it took four days in wartime conditions and we had to sit up the whole of the last night. We left from Melbourne on the “Rangitiki” in April 1945. We had three weeks in Wellington where the ship broke down and we were very well entertained by the kind people there. Crossing the Pacific we encountered an enormous storm, the ship literally climbing up the side of waves you could not see over. As with the bombing though, I was not afraid as by this time I could swim. We not only had storms to worry about but mines and torpedoes were still a threat and the daily drills and need to have life jackets with us at all times reminded us of this. The life jackets came with a survival pack of chocolate and milk tablets, whistle and torch. With in a week the former were eaten and the battery of the later used up. Only the whistle remained. The older boys led a wild life on board - I remember them sliding down the ventilation tubes into the hold.

On the 8th May, VE day, we crossed the date line and therefore had a double celebration as we had two Tuesdays, both May the 8th. I still have the menu from dinner signed by all at our table and for wartime a pretty magnificent meal it was.

The Panama Canal was awe inspiring and the lakes beautiful-my mother and I sailed through right in the point of the bow of the ship. At Panama she bought a huge hand of bananas, a few of which survived till England and made us very popular with people who hadn’t seen one in months.

The ship then turned north and we got very cold before it turned across the Atlantic and headed for Liverpool. Entering the Mersey was a terrible experience to those who had been comparatively sheltered from seeing the devastation of war. I counted forty two sunken ships in the approaches and the docks and dockers looked battered and shabby, everything very grey after Australia.

We were home and with our family but the last months until VJ day were hard for my mother. She had had no news of my father for some time and yet everyone around was celebrating as if the war was over. But we were among the lucky ones- my father came safely home. Although his health was damaged and he died young we had nearly twenty years denied many others.

Alison's father Max was awarded the MBE for Services to Prisoners of War. With his brother Donald he had, at great risk, kept a secret radio in captivity and distributed news. The Webber family returned to Malaya post war. During the Malayan Emergency, Max again faced great danger as a Resettlement Officer in Selangor. In 1952 he was awarded the Selangor Conspicuous Gallantry Medal by the Sultan, for saving the life of a wounded police lieutenant during a terrorist ambush on the Jeram-Merbau estates road, Kuala Selangor.