History

The Malayan Volunteer Forces

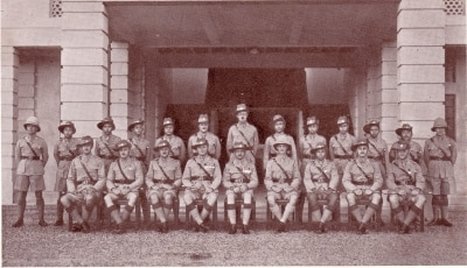

As was the case with other British Colonies there were people in Malaya who realised that they should be at least partially responsible for their own defence. And so the first of the Volunteer Forces of Malaya originated in 1854 at the time of the Crimean War with the enrolment of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps. With their proud motto "In Oriente Primus' Volunteers continued to serve the Crown in Malaya and the Straits Settlements at times of other national crisis. The Boer War of 1899-1902 further stimulated the Volunteer movement with the formation of the Malay States Volunteer Rifles. In 1888 the Singapore Volunteer Artillery Corps was formed. The outbreak of World War 1 in August 1914 led to an immediate and rapid increase in the enrolment of Volunteers who the following year took part in the suppression of the Sepoy Mutiny in Singapore.

As was the case with other British Colonies there were people in Malaya who realised that they should be at least partially responsible for their own defence. And so the first of the Volunteer Forces of Malaya originated in 1854 at the time of the Crimean War with the enrolment of the Singapore Volunteer Rifle Corps. With their proud motto "In Oriente Primus' Volunteers continued to serve the Crown in Malaya and the Straits Settlements at times of other national crisis. The Boer War of 1899-1902 further stimulated the Volunteer movement with the formation of the Malay States Volunteer Rifles. In 1888 the Singapore Volunteer Artillery Corps was formed. The outbreak of World War 1 in August 1914 led to an immediate and rapid increase in the enrolment of Volunteers who the following year took part in the suppression of the Sepoy Mutiny in Singapore.

As war clouds gathered in Europe in the 1930s many men of all walks of life and nationalities [European, Malay, Chinese, Indian and Eurasian] joined the Volunteer Forces. They came from all branches of the Malayan Government Service, from the Mines and Plantations, from the business communities, from the Medical Profession and from the Church. Many other civilians who would have joined the Volunteers, were prevented from doing so because they were in so-called 'reserved occupations' considered essential for the continued smooth running of the country. Whatever their background, they were motivated by a profound sense of wanting to do everything in their power to defend the Crown Colony of Malaya and her dependents.

The men remained in their civilian employment and received military training at night and on weekends. At this time the forces were reorganised along the lines of the British Territorial Army. Officers held a Governor's Commission instead of a King's Commission.

The units of the force were based on the administrative area of Malaya in which the men worked and had enrolled:

The men remained in their civilian employment and received military training at night and on weekends. At this time the forces were reorganised along the lines of the British Territorial Army. Officers held a Governor's Commission instead of a King's Commission.

The units of the force were based on the administrative area of Malaya in which the men worked and had enrolled:

1. The Crown Colony of the Straits Settlements (S.S.)

The Straits Settlements were administered by a British Governor ((Sir Shenton Thomas) who was also High Commissioner for the eleven Malay States. The Straits Settlements consisted of Singapore, Penang and the Province Wellesley, and Malacca (and Labuan and Christmas Island). Volunteers were organised into 4 Battalions:-

Singapore - 1st and 2nd Battalion S.S.V.F [1250 men]

Penang & Province Wellesley - 3rd Battalion S.S.V.F. [916 men]

Malacca - 4th Battalion S.S.V.F. [675 men]

The Straits Settlements were administered by a British Governor ((Sir Shenton Thomas) who was also High Commissioner for the eleven Malay States. The Straits Settlements consisted of Singapore, Penang and the Province Wellesley, and Malacca (and Labuan and Christmas Island). Volunteers were organised into 4 Battalions:-

Singapore - 1st and 2nd Battalion S.S.V.F [1250 men]

Penang & Province Wellesley - 3rd Battalion S.S.V.F. [916 men]

Malacca - 4th Battalion S.S.V.F. [675 men]

2. The Federated Malay States (F.M.S.)

These States were ruled by Sultans, but each had a British Resident to whom they were accountable.The Federated Malay States consisted of Perak, Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang. Volunteers from these States were also organised into 4 Battalions:

Perak - 1st Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Selangor - 2nd Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Negri Sembilan - 3rd Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Pahang - 4th Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

There was also an F.M.S.V.F. Signals Battalion, F.M.S.V.F.Light (Artillery) Battery, F.M.S.V.F. Reserve Motor Transport Company and F.M.S.V.F. Field Ambulance units.

F.M.S.V.F. = Federated Malay States Volunteer Force. Total number of men: 5,200.

These States were ruled by Sultans, but each had a British Resident to whom they were accountable.The Federated Malay States consisted of Perak, Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang. Volunteers from these States were also organised into 4 Battalions:

Perak - 1st Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Selangor - 2nd Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Negri Sembilan - 3rd Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

Pahang - 4th Battalion F.M.S.V.F.

There was also an F.M.S.V.F. Signals Battalion, F.M.S.V.F.Light (Artillery) Battery, F.M.S.V.F. Reserve Motor Transport Company and F.M.S.V.F. Field Ambulance units.

F.M.S.V.F. = Federated Malay States Volunteer Force. Total number of men: 5,200.

|

3. Each of these States was ruled by a Sultan and each had a British Advisor with far less influence than the British Residents of the F.M.S. These 5 States were Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Trengganu and Perlis. Apart from Johore, they were the more northerly States with fewer Europeans and more tenuous lines of communication. Volunteers from these States were, perhaps, less well organised, again with the exception of Johore, and deployed into Local Defence Corps or Forces, rather than Battalions with a more formal command structure. Volunteers were organised into the following groups:

Johore - J.V.E. (Johore Volunteer Engineers) - 258 men. Kedah - K.V.F. (Kedah Volunteer Force) - 571 men. Kelantan - K.V.F. (Kelantan Volunteer Force) - 136 men. Trengganu & Perlis - no regular Defence Force or Corps. |

As well as these Volunteer groupings, there were also Local Defence Corps formed in September 1940, similar to the Home Guard, throughout Malaya. There was also MAS, the Medical Auxilliary Service, and we would include as 'Volunteers' the full time, professional nurses of the Colonial Nursing Service.

Some Malayan Volunteers joined:

Some Malayan Volunteers joined:

- The Malayan Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve ( M.R.N.V.R.) - 1083 men.

- The Malayan Volunteer Air Force (M.V.A.F.) - 350 men.

- The Armoured Car Squadrons under S.S. & F.M.S. commands. In the final days the F.M.S.V.F Armoured Car units were amalgamated and given regimental status.

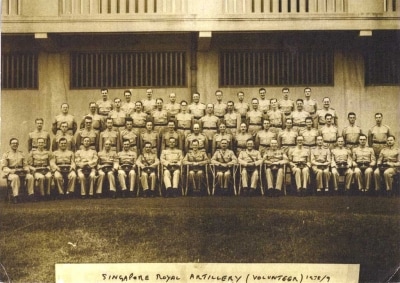

- The Singapore Royal Artillery and Singapore Royal Engineers.

SOE - particularly in the form of Stay Behind Parties. Volunteers participating in these were given General List Commissions.Others received regular commissions in the two battalions of the Malay Regiment.

During the Malayan Campaign the FMSVF under Brigadier Moir acted as Lines of Communications troops defending airfields, road junctions, bridges etc. They took part in the successful delaying action at the Battle of Kampar and the FMSVF Light Battery and Armoured Cars fought with distiction both on the mainland and at Singapore.

At the surrender of Singapore there were more than 18,000 Volunteers in the armed forces,most of whom were imprisoned as military personnel, although some were imprisoned as civilians along with many non-native women and children who had not been able to escape from Singapore.

With considerable local knowledge the Volunteers were of enormous help to the thousands of captured British Forces, especially those who had only been in the Far East for a matter of weeks before capture. They knew and understood the local languages and the people, particularly those who remained loyal to the British and wanted to help them. They were acclimatised to the conditions, which must have been difficult to adjust to for the newly arrived troops - most of whom had received no training in jungle warfare.They understood the prevalent diseases such as Malaria and Dengue Fever, how best to avoid them, and the medicines that were needed to control them. They were able to barter with the local traders for food and medicine, and to set up a system of 'listening posts' for information, especially in the early months of imprisonment.

Even in Thailand, while building the infamous Burma/Siam Railway, some of the Volunteers were able to speak Thai and make contact with the local Thai / Thai Chinese population, to get the extra food and medicines so urgently needed by the starving and desperately ill prisoners of war.

When the Volunteers and other FEPOWs were finally repatriated to Britain late in 1945, and returned home to their loved ones, Europe had been at peace for over 4 months. There was a sense of purpose in the country, and a great determination to put the memories of the last six years of war behind them, so that people could get on with their lives and look forward to a brighter future.

It was into this atmosphere of optimism that the FEPOWs, including the Volunteers, returned. How devastating it must have been for them that no-one wanted to know about their ordeals and experiences, or could understand what they had been through. Indeed, most people in this country had been (and still are) totally unaware of the harrowing time the FEPOWs had endured - the murders, the tortures, the deprivations, the sheer and utter brutality of an alien foe - and they didn't want to start hearing about it. In fact, the general impression was that the FEPOWs had been languishing in some kind of luxurious holiday camp in the Far East, while their kith and kin had been enduring the horrors of the Blitz on the Home Front, and the D-Day Landings in Europe.

During the Malayan Campaign the FMSVF under Brigadier Moir acted as Lines of Communications troops defending airfields, road junctions, bridges etc. They took part in the successful delaying action at the Battle of Kampar and the FMSVF Light Battery and Armoured Cars fought with distiction both on the mainland and at Singapore.

At the surrender of Singapore there were more than 18,000 Volunteers in the armed forces,most of whom were imprisoned as military personnel, although some were imprisoned as civilians along with many non-native women and children who had not been able to escape from Singapore.

With considerable local knowledge the Volunteers were of enormous help to the thousands of captured British Forces, especially those who had only been in the Far East for a matter of weeks before capture. They knew and understood the local languages and the people, particularly those who remained loyal to the British and wanted to help them. They were acclimatised to the conditions, which must have been difficult to adjust to for the newly arrived troops - most of whom had received no training in jungle warfare.They understood the prevalent diseases such as Malaria and Dengue Fever, how best to avoid them, and the medicines that were needed to control them. They were able to barter with the local traders for food and medicine, and to set up a system of 'listening posts' for information, especially in the early months of imprisonment.

Even in Thailand, while building the infamous Burma/Siam Railway, some of the Volunteers were able to speak Thai and make contact with the local Thai / Thai Chinese population, to get the extra food and medicines so urgently needed by the starving and desperately ill prisoners of war.

When the Volunteers and other FEPOWs were finally repatriated to Britain late in 1945, and returned home to their loved ones, Europe had been at peace for over 4 months. There was a sense of purpose in the country, and a great determination to put the memories of the last six years of war behind them, so that people could get on with their lives and look forward to a brighter future.

It was into this atmosphere of optimism that the FEPOWs, including the Volunteers, returned. How devastating it must have been for them that no-one wanted to know about their ordeals and experiences, or could understand what they had been through. Indeed, most people in this country had been (and still are) totally unaware of the harrowing time the FEPOWs had endured - the murders, the tortures, the deprivations, the sheer and utter brutality of an alien foe - and they didn't want to start hearing about it. In fact, the general impression was that the FEPOWs had been languishing in some kind of luxurious holiday camp in the Far East, while their kith and kin had been enduring the horrors of the Blitz on the Home Front, and the D-Day Landings in Europe.

|

At first, very few books were written about the horrors of the Far East War. No one wanted to re-live their unendurable experiences and for those who returned to Malaya it was devisive to do so for there were three entirely different wartime experiences: those who had stayed and become FEPOWs, those who had escaped or been evacuated, and the newcomers who were often young men who had experienced a successful war in Burma or Europe. However, in recent years more books have been written so that younger generations will know what happened to their grandfathers, uncles and cousins. A small proportion of these recent publications have been written by Volunteers, who were treated in the same way as other members of the British Forces, by the Japanese.

|

Some good reading on the Volunteers

In Oriente Primus: A History of the Volunteer Forces in Malaya & Singapore by Jonathan Moffatt & Paul Riches. Details from [email protected]

Captain Jack - Surveyor & Engineer - the Autobiography of John Mackie [Bateson Publishing Ltd, New Zealand 2007]

Baba Nonnie Goes to War by Ron Mitchell [Coombe Publishing 2005]. Details from [email protected]

My Life in Four Continents by Noel Disney [memoirs of an FMSVF Volunteer] Postscript Printing, Eltham 2008

The Amonohasidate or the Gate of Heaven by Richard Yardley [self-published 2003]

The Rainbow through the Rain by Geoffrey Scott Mowat [New Cherwell Press 1995,2005].

Volunteer by Paul Gibbs Pancheri [self published 1995]

Bamboo Doctor by Dr Stanley Pavillard [Macmillan & Co. London 1960 or Pan Books 1962]

Prisoners of the Emperor by Ian Mitchell [Pentland Press 1996]

The Burma Siam Railway: The Secret Diaries of Dr Robert Hardie 1942-1945 by Robert Hardie [Imperial War Museum 1983]

One Fourteenth of an Elephant by Ian Denys Peek [Pan Macmillan, Australia 2003]

I will sing to the End by Ian MacLeod [Coco's Publications 2005]

For the Pre-War history of the Volunteers See: A History of the Singapore Volunteer Corps by Captain T.M. Winsley SVC [Government Printing Office, Singapore 1938]

The Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum holds many diaries and unpublished memoirs by Malayan Volunteers. Particularly recommended are those of J.T. Rea, J.K. Gale, R.J. Godber, Tom Evans.

The National Archives at Kew hold Brigadier Moir's 32 page report on FMSVF Lines of Communication Operations December 1941- February 1942 [CAB 106/156]

My Life in Four Continents by Noel Disney [memoirs of an FMSVF Volunteer] Postscript Printing, Eltham 2008. Copies available from [email protected]

Memories of a Malaccan. The Life and Times of Lim Keng Watt [1909 - 1996] " By Audrey Lim ISBN 978-967-13552-2-0 published by Mindskills Management and Consultancy, Malaysia 2018. [Sgt. Lim Keng Watt served in the Malacca Volunteers Corps].

On Parade. Straits Settlements Eurasian men who volunteered to defend the Empire 1862-1957." By Mary Anne Jansen, John Geno-Oehlers, Ann Ebert Oehlers. ISBN 978-981-11-8729-2. Published by Singapore Management University 2018.

In Oriente Primus: A History of the Volunteer Forces in Malaya & Singapore by Jonathan Moffatt & Paul Riches. Details from [email protected]

Captain Jack - Surveyor & Engineer - the Autobiography of John Mackie [Bateson Publishing Ltd, New Zealand 2007]

Baba Nonnie Goes to War by Ron Mitchell [Coombe Publishing 2005]. Details from [email protected]

My Life in Four Continents by Noel Disney [memoirs of an FMSVF Volunteer] Postscript Printing, Eltham 2008

The Amonohasidate or the Gate of Heaven by Richard Yardley [self-published 2003]

The Rainbow through the Rain by Geoffrey Scott Mowat [New Cherwell Press 1995,2005].

Volunteer by Paul Gibbs Pancheri [self published 1995]

Bamboo Doctor by Dr Stanley Pavillard [Macmillan & Co. London 1960 or Pan Books 1962]

Prisoners of the Emperor by Ian Mitchell [Pentland Press 1996]

The Burma Siam Railway: The Secret Diaries of Dr Robert Hardie 1942-1945 by Robert Hardie [Imperial War Museum 1983]

One Fourteenth of an Elephant by Ian Denys Peek [Pan Macmillan, Australia 2003]

I will sing to the End by Ian MacLeod [Coco's Publications 2005]

For the Pre-War history of the Volunteers See: A History of the Singapore Volunteer Corps by Captain T.M. Winsley SVC [Government Printing Office, Singapore 1938]

The Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum holds many diaries and unpublished memoirs by Malayan Volunteers. Particularly recommended are those of J.T. Rea, J.K. Gale, R.J. Godber, Tom Evans.

The National Archives at Kew hold Brigadier Moir's 32 page report on FMSVF Lines of Communication Operations December 1941- February 1942 [CAB 106/156]

My Life in Four Continents by Noel Disney [memoirs of an FMSVF Volunteer] Postscript Printing, Eltham 2008. Copies available from [email protected]

Memories of a Malaccan. The Life and Times of Lim Keng Watt [1909 - 1996] " By Audrey Lim ISBN 978-967-13552-2-0 published by Mindskills Management and Consultancy, Malaysia 2018. [Sgt. Lim Keng Watt served in the Malacca Volunteers Corps].

On Parade. Straits Settlements Eurasian men who volunteered to defend the Empire 1862-1957." By Mary Anne Jansen, John Geno-Oehlers, Ann Ebert Oehlers. ISBN 978-981-11-8729-2. Published by Singapore Management University 2018.